Black Racialization / Erasure

Erasing Black Voices

Philip S. Warne (1843-1892), the author of Tiger Dick, the Faro King; Or, the Cashier’s Crime, is the only known dime novel writer of African descent. Warne wrote over 50 serials—mostly “romantic adventures” for the Beadle and Adams publishing house.33 Since he submitted most of his materials by mail, the publishers had no idea Warne was white and African American, but when he visited editor Orville Victor in New York City, Victor told him to leave and never return. There is evidence to suggest that Warne may have died by suicide after meeting with the dime novel publisher.34

Seemingly positive Black figures in dime novels are usually cast as virtuous, self-sacrificing, and submissive. The protagonist of Darkie Dan, the Colored Detective; Or, the Mississippi Mystery: A Romance of the Sunny South is a model of these qualities. Darkie Dan is not a detective, but a Black man who is enslaved. At fifteen he saves Gertrude Delamere from a pack of wolves. In return, her father Fenton Delamere, “frees” Dan by moving him to “the mansion” to have Dan serve as his “especial valet.”35 A former Confederate general Delamere acknowledges that Dan is “noble” and has “a heart that most white men might be proud of,” but the plantation owner “loses” Dan in a card game.36 No matter the circumstance, Dan remains loyal to the Delamere family—even though Delamere puts his life in mortal danger more than once. Dan “refuse[s] to meddle in politics” and is viewed as one of the “‘shining lights’ of his race.”37

Written by Prentiss Ingraham (1843-1904)—a confederate soldier, mercenary, and author of more than 600 dime novels—this narrative “recast[s] the exploitati[on]” of slave-holding in the U.S. history to maintain the interests of “white supremacy and black subjugation.”38 White bodies were legally allowed to perpetrate crimes against black bodies when slavery was legal in the U.S., but this dime novel was published in 1881, almost 17 years after the 13th Amendment was ratified. Delamere is seen to have “a presumed cause and rationale” for his behavior with regard to how he treats Dan, no matter how egregious that behavior is.39 However, Dan never loses his patience or his temper; he is perfectly submissive to Delamere’s needs. Dan’s nobility is dependent on this subjugation to Delamere, no matter the former general, plantation owner, and gambler’s words or deeds.

33 Marlena E Bremseth, Tiger Dick (1875) Spotlight, Spotlight: Nickels and Dimes from the Collections of Johannsen and LeBlanc, Northen Illinois University, 2020. https://dimenovels.lib.niu.edu/learn/spotlights/tigerdick

34 Bremseth, Tiger Dick. https://dimenovels.lib.niu.edu/learn/spotlights/tigerdick

35 Prentiss Ingraham, Darkie Dan, the Colored Detective; Or, the Mississippi Mystery: A Romance of the Sunny South, Beadle's New York Dime Library, vol. 11 no. 135 (New York, NY: Beadle and Company, 1881), 2.

38 Janell Hobson, Body as Evidence: Meditating Race, Globalizing Gender (New York, SUNY Press, 2012), 70.

39 Hobson, Body as Evidence, 71.

Co-Opting The Black Female Body

In Maum Guinea and Her Plantation “Children”; Or, Holiday-Week on a Louisiana Estate: A Slave Romance, the author Metta V. Victor introduces the special double issue with a claim that the stories told within are an honest account of Black people and slavery.40 The relationship between Rose and Hyperion—who are enslaved--takes centerstage, but this issue also recounts stories that focus on “the selling of children and families separated.”41 In Rose’s case she is to be sold to a man who wants to keep her as his concubine; she pleads with Virginia, the White woman to whom she is enslaved, to save her from this fate. Virginia can only see her own need and states, “If papa has sold you, he has done very wrong…. He knows I can not do without.”42 Maum Guinea attempts to help Rose and Hyperion escape, but the issue ends with Rose and Hyperion married and enslaved. In this regard, the narrative is “schizophrenic” in its depiction of a “proslavery/antislavery ‘romance of fact’.”43

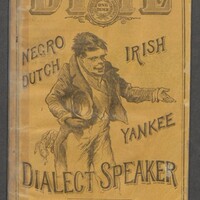

In both Maum Guinea and Darkie Dan, there are Black characters who are referred to as mulatto or quadroon, discriminatory terms “that collapse mixed‑race bodies into blackness [and] operate in the ongoing erasure of ‘evidence’ of rape and interracial sexual liaisons involving black women.”44 In addition to dime novel stories, publishers like Beadle & Adams also published dime novel songbooks and dialect books. The songbooks included songs from minstrel shows that depicted mixed-race Black women as sexually available. Eric Lott argues that minstrel shows were more than “cultural robbery,” but a place of “conflictual intensity for the politics of race, class, and nation.”45 Dime novel publishers promoted racial stereotypes that exploited the real-life experiences of Black women, romanticizing the sexual violence that was part of these women’s daily lives.

40 Melissa Adams-Campbell, Maum Guinea (1861) Spotlight, Spotlights: Nickels and Dimes, from the Collections of Johannsen and LeBlanc, Northern Illinois University, 2020. https://dimenovels.lib.niu.edu/learn/spotlights/maumguinea

41 Adams-Campbell, Maum Guinea. https://dimenovels.lib.niu.edu/learn/spotlights/maumguinea

42 Metta V. Victor, Maum Guinea, and Her Plantation "Children"; Or, the Holiday-Week on a Louisiana Estate: A Slave Romance, Beadle's Dime Novels, no. 33 (New York, NY: Beadle and Company, 1861), 118.

43 Mason Stokes, The Color of Sex: Whiteness, Heterosexuality, and the Fictions of White Supremacy (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2001), 57.

44 Janell Hobson, Body as Evidence: Meditating Race, Globalizing Gender (New York: SUNY Press, 2012), 69-70.

45 Eric Lott, Love and Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class (Oxford: Oford University Press, 1993; 2013), 8.