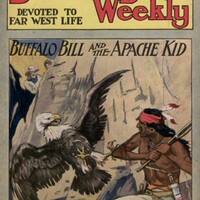

Indigenous Racialization / Erasure

Villainizing Native American Autonomy

In Dingle, the Outlaw; Or, the Secret Slayer, three hunters sit around a campfire contemplating “the cussed Shawnee Injun, Tecumseh” who had been “stirrin’ up the southern tribes ag’in the whites” even though they understand that “the reds” have “been wronged by the whites.” 26 This narrative takes place in the early 1800s, when the Shawnee chief Tecumseh (1768-1813) attempted to unite Indigenous communities against U.S. westward expansion.

Between 1814 and 1816, the price of cotton had doubled on “the world market.”27 Plantation owners wanted to occupy Indigenous homelands east of the Mississippi to increase their profits. Once the Indian Removal Act of 1830 was signed by President Andrew Jackson, Creeks, Seminoles, Choctaw, Cherokee and other Indigenous communities were removed—sometimes forcibly and in chains—to places west of the Mississippi that the U.S. designated as “Indian territories."28 This removal resulted in the deaths of thousands of Indigenous people. The Trail of Tears, as the forced march is called, covers 5,043 miles and runs through nine states—Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, and Tennessee.29

Empathy for Tecumseh and the Indigenous community is only a brief mention in Dingle, the Outlaw. Both Dingle’s outlaws and the Shawnee people are antagonists to the hunters who are searching for a white settler’s daughter who has been kidnapped by the outlaws. The person who saves her is another female, Leonola, whose family had been killed by the same criminals. Leonola escapes and the Shawnee take her in. Leonola, whose mother was Shawnee and father was English, never returns to the British settlement; instead, she chooses vengeance. One-by-one, she murders the outlaws who have slaughtered her family. When she kills the last of the outlaws, partly to save the kidnapped girl, Leonola is shot and dies.

Mahaska, the Indian Princess also has a female character whose mother is Indigenous of an unnamed heritage. In this case, Mahaska is called Katherine by her father and viewed as a “half-savage child” who has the energy of “a young panther.”30 She leaves white society and returns with her grandmother Ahmo to take her place as an “Indian Princess.”31 This leaving is seen as “vengeance” and betrayal.32 Both dime novel issues erase what these young women’s mothers’ relationships to their white fathers might have been and skew real-life relationships between Indigenous and white populations like the real-life figure of Mary Jemison (1743-1833). Jemison had been kidnapped and her parents murdered by the Shawnee, but she chose to stay with the Seneca community who adopted her and rejected British colonial society.

26 Edwin Amerson, Dingle, the Outlaw; Or, the Secret Slayer, Beadle's New Dime Novels, nos. 608 & 287 (New York, NY: Beadle and Adams, 1885), 10-11.

27 Donna L. Akers, Living in the Land of Death: The Choctaw Nation, 1830-1860 (Michigan: Michigan University Press, 2004), 22.

28 "Trail of Tears: Plan Your Visit," National Park Service, July 28, 2020. https://www.nps.gov/trte/planyourvisit/index.htm

29 "Trail of Tears: Plan Your Visit."

30 Ann S. Stephens, Mahaska, the Indian Princess, Beadle's Dime Novels, no. 63 (New York, NY: Beadle and Adams, 1863), 6-7.