Between 1860 and 1915, over fifty-thousand dime-novel serials were published in the United States. These paperbound ephemera sold for five, ten, or fifteen cents an issue. In the 1860s, Beadle & Adams coined the term dime novel as a brand name for one of the publishing house’s serials, but the phrase became synonymous with cheap reading entertainment. Dime novels were classified as newspapers or weekly news supplements to avoid book rate postage, making distribution inexpensive, but in 1909 the post office succeeded in a reclassification that made the process too expensive.1 Production for the dime novel as it was known all but stopped by 1915.

Publishing houses like Street & Smith, the publishers of The New Nick Carter Weekly, did pay handsomely for well-known authors’ bylines, but they also used pseudonyms to avoid paying high author fees. For instance, the character of Nick Carter was created by John R. Coryell in 1886 for New York Weekly, but the more than 1,400 issues devoted to the dime novel detective Nick Carter were written by upwards of thirty authors with their bylines usually attributed to the fictional detective or his partner Chick Carter.

Illustrators like N.C. Wyeth, father to painter Andrew Wyeth, got their start drawing dime novel covers, but it is difficult to document who created them since illustrators rarely signed their name to a work and no records were kept. According to J. Randolph Cox, “Publishers often used the same artist for all of their publications; such an artist might have to work rapidly to produce several covers each week."2 Sometimes too a cover was drawn before a story was written, and authors were asked to write a narrative that matched the image.

In Mechanic Accents: Dime Novels and Working-Class Culture in America, Michael Denning argues that dime-novel readers were in the majority “young workers, often of Irish or German ethnicity, in the cities and mill towns of the North and West” and dime novels “were seen as the purview of the working class.”3 If dime novels were written with the working class in mind, it was a white working class since the stories propagated fear and loathing of those who were considered not white. The protagonists at the center of dime novel narratives were mostly white men who always triumphed in any conflict with immigrant, Indigenous, and Black Americans.

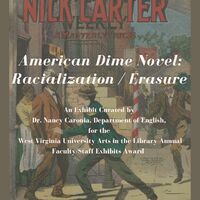

The dime novel covers and song book text curated for American Dime Novel: Racialization / Erasure reveal how a popular literary entertainment reinforces already established ethnic and racial stereotypes. The caricatures on the covers of these dime novels show immigrants, Indigenous, and Black Americans as violent murderers and thieves or ignorant fools. They are most often written as antagonists for or servants to the White protagonist of the dime novel. These depictions normalize juridical and political actions like the Indian Removal Act, the Chinese Exclusion Act, and Jim Crow or mob justice like the lynching of 19 Italians in New Orleans in 1891.

1 Michael Denning, Mechanic Accents: Dime Novels and Working-Class Culture in America (London: Verso, [1987] 1998), 19.

2 Randolph J. Cox, The Dime Novel Companion: A Sourcebook (Greenbook Press, 2000), xviii.

3 Denning, Mechanic Accents, 45-46.

Visit the WVU Art in the Libraries Exhibit:

American Dime Novel: Racialization / Erasure

Fall 2021

West Virginia University Downtown Library

DCL Room 1020

Public Lecture on Thursday, November 4, 2021 @ 4:00pm in DCL Room 1020 with Dr. Nancy Caronia

NOTE: This exhibit may illuminate, challenge, unsettle, confound, provoke, and, at times, upset. Please be advised that depictions of ethnicity and race as well as the political and ethical positions found within these pieces may be disturbing or offensive for some viewers.