Italian Racialization / Erasure

The Criminal Body: Italian Racialization

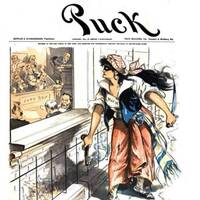

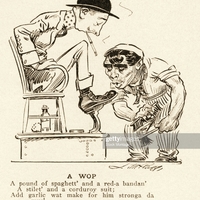

Political cartoons are social commentary that rely on standard symbols like Uncle Sam or Lady Liberty to evoke concepts such as patriotism and nativism. They also use caricatures to easily code individuals or groups of people like immigrants or politicians. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, political cartoonists such as Louise Dalrymple (1866 – 1905) often portrayed Italian immigrants as violent and vulgar murderers and thieves, aligning with the editorial viewpoints of newspapers and magazines.

For instance, on March 5, 1882, The New York Times ran an article depicting Southern Italian immigrants as “low and ignorant” with a penchant for “fighting, violence, and attempts at murder.”4 Less than 10 years later and despite a lack of evidence, 19 Sicilians were charged with the murder of New Orleans Police Chief Hennessey. After the first trial, the first 9 defendants were acquitted, but continued to be held in the jail for their protection. A mob stormed the jail and lynched 11 of the 19 Sicilians. The New York Times called the lynching “justified.”5 The editors of Leslie’s Weekly suggested “the eleven Sicilian prisoners” must have “on general principles deserve[d], and no doubt expected, to meet a violent death” due to their membership in “the lowest criminal classes.”6

4 "Our Future Citizens," The New York Times, March 5, 1882, 6.

5 "Chief Hennessy Avenged: Eleven of His Italian Assassins Lynched by a Mob," The New York Times, Mar. 15, 1891, 1.

6 Salvatore J. LaGumina, WOP!: A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination in the United States (Toronto: Guernica, 1999), 84.

From Italian Unification to U.S. Immigrant Criminal

Dime novels established Southern Italian immigrant criminality as an inborn character trait as early as 1872, when the antagonist Guido Montazio, a murderer and thief who abandons his pregnant Anglo-Saxon American wife, makes an appearance in the dime novel issue The White Outlaw; Or, the Branded Brigand. Although it’s mentioned that Montazio is a “political refugee from sunny Italy,” his status is never clarified; instead, the term refugee is linked to criminal behavior.7

By 1871 the Kingdom of Italy had united smaller kingdoms and duchies to become one nation-state. The Unification, or Risorgimento, as it is known in Italy, created an economic disparity between the north and south of the new country with those from the poorer southern region often being labeled brigands—criminals. Historian Maddalena Tirabassi notes that after unification “seventy-five percent of the national income was generated in the [northern] territories of Liguria, Piedmont, Lombardy, and the Veneto” where only a third of the population lived.8 When the new government was formed, it was the northern territories that dominated policymaking, and those in the south were left without “public works programs, transportation improvements, educational reforms, and badly needed irrigation projects.”9 Taxes and mortgage rates were raised and the contadini (peasants) were forced to take on debt to maintain subsistence-living conditions.10

Southern Italians looked to mitigate their circumstances by migrating to the U.S. Before 1924, there were no national immigration laws to keep Italians from entering the U.S. It was not until The Immigration Act of 1924 that Italians and other European immigrants were limited from entering the U.S. through a national origins quota.

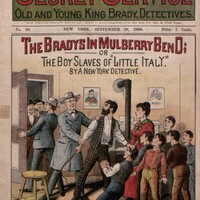

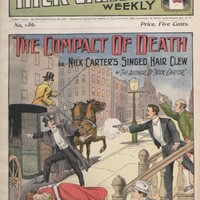

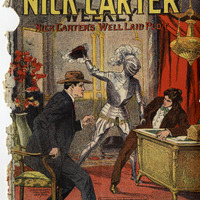

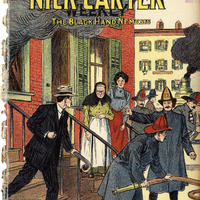

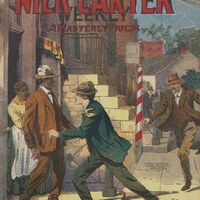

Dime novels engaged with the arrival of Southern Italian immigrants by criminalizing them. No matter the series or publishing house, criminality became the standard behavior for any Southern Italian character found within the pages of a dime novel. In dime novel detective fiction, detectives like Nick Carter or Old King Brady upend entire criminal organizations through the use of disguises and their ability to enter into any immigrant neighborhood without notice. When these detectives put on Italian laborer or mafiosi costumes, their fictional masks reinforce a racialized image of a wholly brutal, ignorant, and anti-American people.

7 Harry Hazard [pseud.], The White Outlaw, Or, the Branded Brigand, Beadle's New Dime Novels 1, no. 256 (New York, NY: Beadle and Adams, 1872), 71.

8 Maddalena Tirabassi, "Why Italians Left Italy: The Physics and Politics of Migration, 1870--1920" in The Routledge History of Italian Americans, ed. William J. Connell & Stanislao G. Pugliese (New York: Routledge, 2018), 117-131, at 117.

9 Peter Vellon, A Great Conspiracy Against our Race: Italian Immigrant Newspapers and the Construction of Whiteness in the Early 20th Century (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 16.

10 Tirabassi, "Why Italians Left", 117.

Joseph Petrosino: Real Life Nick Carter

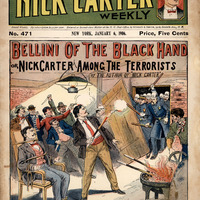

On July 24, 1909, The New Nick Carter Weekly dime-novel serial released The Black Hand; Or, Chick Carter’s Well-Laid Plot, a narrative focused on Carter and his assistant Chick Carter as they infiltrate and break up “a menace” brought about by “a certain class of Sicilian [immigrants] who are objectionable in every way.”11 Before the Carters embark on the case, the real-life assassination of New York City police Lt. Giuseppe “Joe” Petrosino is mentioned. Petrosino’s assassination is viewed as a “terrible outrage against the law and against all humanity,” and Carter notes “the whole world was shocked.”12 The real life lieutenant is not mentioned again.

Born in Padula (Campania), Italy, Petrosino joined New York City’s police force in 1883, becoming its first detective of Italian descent. As the head of a twenty-five-man Italian Squad, Petrosino was called a “master of disguises” who understood and spoke numerous Italian dialects.13 Petrosino thwarted many extortion rings, including one targeted at famed tenor Enrico Caruso. The detective disguised himself as the opera singer and caught the extortionists. He also warned of an assassination plot against President McKinley’s life. The detective’s information went unheeded and on September 6, 1901, McKinley was murdered.

On March 12, 1909 Petrosino was assassinated. He had been “gathering evidence [in Palermo, Sicily] to seek the extradition of … [Italian] gangsters who had immigrated to New York.”14 At his death, The New York Times wrote that Petrosino “was a man of uncommon courage and determination.”15 President Theodore Roosevelt stated that the lieutenant “did not know the name of fear.”16 The New York Times’ front-page headline noted “200,000 Citizens Line Streets” to pay their respects at his funeral.17

While dime-novel detectives, especially Nick Carter, have been accepted as masters of disguise, Petrosino’s language fluidity, his understanding of international law and politics, and the crime-fighting techniques he developed through the Italian Squad are undertaken by the Carters. Although Petrosino had been mentioned in previous issues before his murder, he was never cited as a direct or indirect influence.

The 1906 silent film The Black Hand, touted as the first gangster film, is based on a case that Petrosino solved, but he is not mentioned in the credits. There have been a number of movies made about Petrosino’s life, including the now-lost 1912 full-length silent film The Adventures of Lieutenant Petrosino; the 1960 Pay or Die!, which starred Ernest Borgnine as the lieutenant; and the 1950 Black Hand. Leonardo DiCaprio is currently slated to star as Petrosino in an adaptation of Stephan Talty’s The Black Hand: The Epic War Between a Brilliant Detective and the Deadliest Secret Society in American History (2017).

11 Nick Carter [pseud.], The Black Hand; Or, Chick Carter's Well-Laid Plot, The New Nick Carter Weekly 1, no. 656 (New York: Street & Smith) 1909), 1.

13 Selwyn Raab, Five Families: The Rise, Decline and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires (New York: St. Martin's Press,2006), 20.

14 Antonio Nicaso, "Organized Crime and Italian Americans" in The Routledge History of Italian Americans, ed. William J. Connell and Stanislao G. Pugliese (New York: Routledge, 2018), 479-492, at 482.

15 "The Murder of Petrosino," The New York Times, April 13, 1909, 1.

16 Nicaso, "Organized Crime," 482.

17 "Petrosino Buried with High Honors," New York Times, April 13, 1909, 1.