Years of Solidarity: Leadup to the Battle

Cultures of Resistance

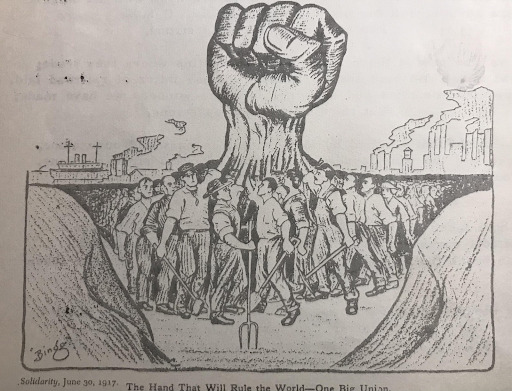

In the lead-up to the Battle of Blair Mountain, many different organized groups were on the scene in West Virginia, working among miners to help set up effective resistance against the status quo. Most of these groups were unions, which helped to organize workers around certain demands. One of these organizations was the International Workers of the World, often abbreviated as the IWW. There was a lot of importance surrounding organization. The miners had to fight in a collective way to get any traction against the large, powerful coal companies. Things such as pro-labor propaganda and labor rallies aided in getting miners organized in thought and action. Here, we can see a pro-labor image printed in an IWW manuscript, which may have been used to inspire miners to organize.

Offering Demands

The miners were fed up with their poor working conditions and mistreatment, and began to band together to fight back against the large coal interests that were running their towns.

The Battle of Blair Mountain was preceded by years of build-up, in which tensions gradually rose as hostility grew between miners and bosses. The Paint Creek miners were some of the first to raise their voices over a specific issue. Their piece rate was significantly lower than piece rates paid in other union areas. The Paint Creek miners reacted by demanding their bosses pay the difference.

This outcry was followed by Cabin Creek miners submitting demands for:

- Union recognition.

- right to free speech and peaceful assembly.

- An end to black-listing union men and compulsory trading at company-owned stores.

- An end to "cribbing" (constructing wooden cribs on the sides of mine cars to make them hold more coal and then paying piecework miners as though the car was ordinary size).

- Installment of scales at all mines.

- The right to check-weighmen selected and paid by the miners.

- Two people to determine "docking" penalties for impurities in the coal that was mined instead of one (Wheeler, 1976).

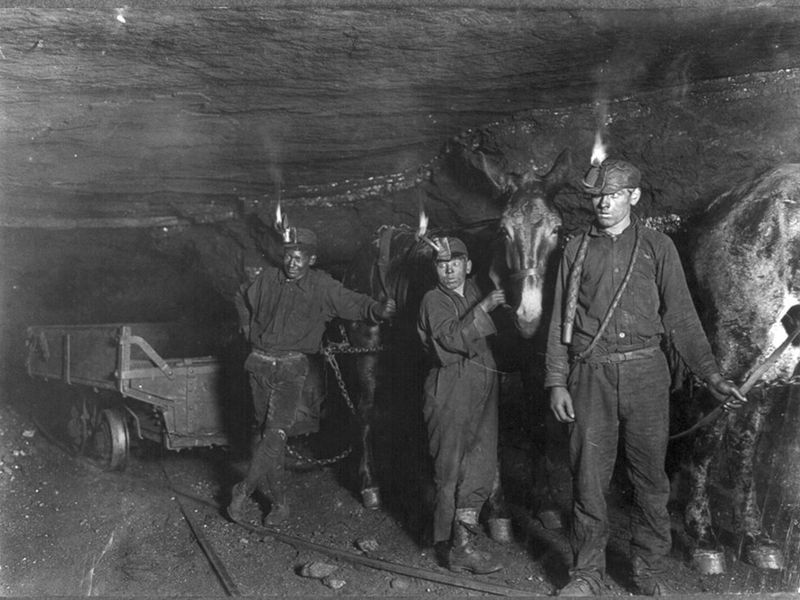

Miners also brought up ethical issues like the use of child labor in mines. Pictured below is a photograph taken in 1908 of underage coal miners pulling equipment with donkeys.

Miners Rally

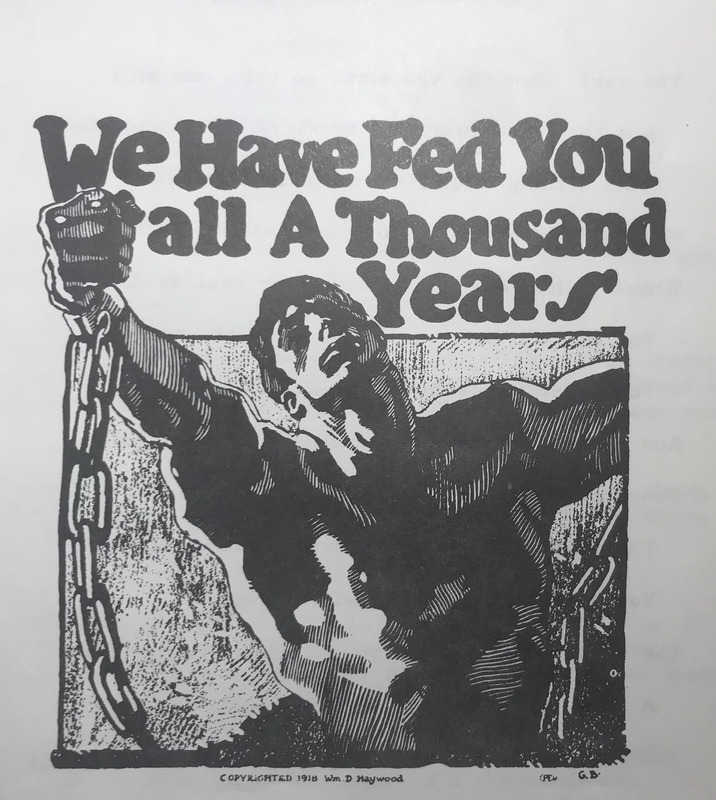

Miners' mindsets began to shift determinately toward dissent. Pro-labor activists like Mother Jones began rallying workers in West Virginia, while miners across West Virginia became conscious of the rights they had been denied and how they might achieve them. The image below shows a fist with a caption that reads "We have fed you all a thousand years." Coal was used to fuel many industries and certainly aided in the distribution of food. Using this rhetoric helped rally others by letting them realize how important the coal miners were to people around the U.S.

Mother Jones, pictured below, was a labor activist who spent her life fighting alongside others for their basic human rights. She worked heavily alongside the West Virginian miners and with many other labor activists to aid in bringing traction to the fight for unionization and fair living conditions. For her work alongside the mine workers, she was convicted for conspiracy to commit murder (Michals, 2015).

The magazine which printed the picture of the fist we featured above was called Solidarity. It was the official organ of the IWW.

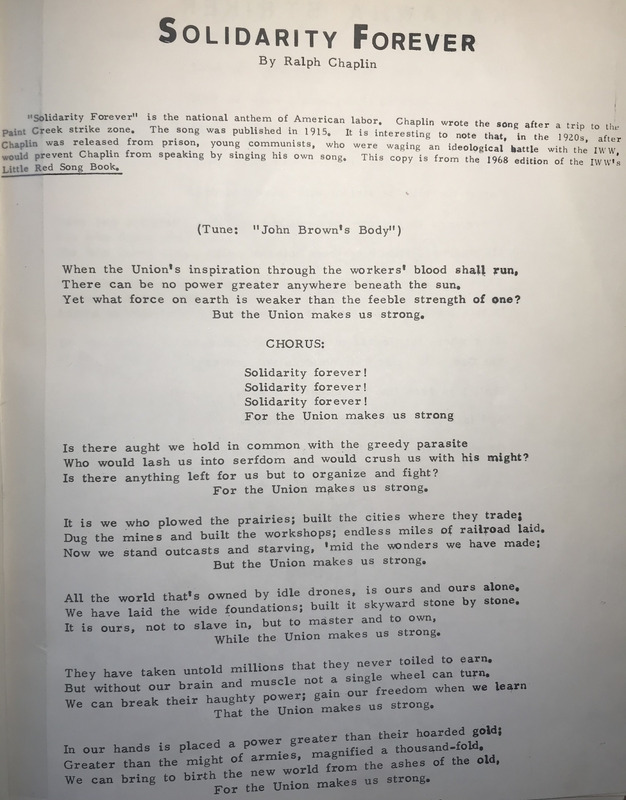

Ralph Capin, who was once editor of Solidarity, spent much of his time in West Virginia working with miners and helping to print The Socialist and Labor Star, the Local Trade and Labor Assembly in Huntington's official newspaper. There, he met Elmer Rumbaugh, a native West Virginian, and worked with him under the paper's editor to write, photograph, and print for the paper. All upper-level staff were also writers for the paper.

He and Rumbaugh worked together to interview miners at the Kanawha strike, and to distribute strike literature. During these trips, the examples of solidarity that they saw inspired Chaplin to write, "Solidarity Forever," perhaps one of the most well-known union hymns in existence, pictured below (Patterson, pp. 2-8, n.d.).

Irreconcilable Differences

The instances of solidarity and organization they saw among the miners included one daring act of cooperation, in which workers at the C&O railway in Huntington would inform strikers in Kanawha of trains with approaching scab labor, or replacements for striking workers. Once informed, the miners would intercept the trains and force the scab labor off. (Patterson, n.d.)

Despite this cooperation and concerted effort by organized groups, abuses of miners' rights continued. One such instance in which striking miners were shown open hostility was the "Bull Moose Special" incident, in which operatives on an armored train carrying machine guns opened fire on a tent city, killing one miner (Lee, 1969) Such violent and destructive hostility against the miners on the part of the government and mine agents was not uncommon, as the offices of the Socialist and Labor Star, were looted and destroyed by the National Guard (Patterson, n.d.). Below is a clipping from the Star describing the incident.

Spillover

With all of these hostilities piling up on one another, things were bound to get out of hand.

On May 19th, 1920, a gunfight broke out between agents of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency and pro-union operatives. The fight was the result of a contract which forced miners to stay out of unions, which the miners were compelled to sign. Sid Hatfield, the town's pro-union sheriff, was involved in the gunfight. (Lee, 1969)

It started when detectives arrived on the scene to evict miners and their families from company housing due to non-compliance. Many families were then forced to vacate their homes because of their association with strikers. However, instead of being allowed to seek shelter elsewhere, they were forced to stay in Matewan. It is unknown who fired first, but the tensions around this issue sparked an intense reaction that led to a shootout (Boissoneault, 2017).

A circular relationship started. Continued abuses by coal companies would create organization, which would inspire abuses by coal companies. This powder keg threatened to blow many times. The Three Days' Battle of the Tug, in which deputy sheriffs attacked a strikers' tent colony along the Tug River (Lee, 1969), was one such possible flashpoint, which got under control quickly. Such tent colonies were set up to house miners who had been kicked out of their company-owned houses for striking. While the situation was quickly brought under control, the reaction by local the government was harsh. In 1921, Governor E. F. Morgan declared Marshall law in response to these events. Below is the text of his proclamation.

"A state of war, insurrection, and riot is, and has been for some time, in existence in Mingo County, and many lives and much property have been destroyed as a result thereof, and riot and bloodshed are rampant and pending. No publication, either newspaper, pamphlet, handbill, or otherwise, reflecting in any way upon the United States, or the State of West Virginia, or their officers, may be published, displayed, or circulated within the zone of martial law." ("A Proclamation by the Governor," 1921, p. 9)

Major Davis, tasked with enforcing martial law, proclaimed assemblages within the strike zone illegal. This measure was enforced only against strikers inspiring such awkward sights as two strikers walking together being expected to keep a distance between themselves (Lee, 1969).

The "Armed March," which turned into the Battle of Blair Mountain, was largely organized to free the people of Southern West Virginia (Lee, 1969). President Frank Keeney of District 17, an organizer among the miners, urged Governor Morgan to lift marshal law. He did not. It was at this point that Keeney gave this address:

"You have no recourse, except to fight. The only way you can get your rights is with a high-powered rifle, and the man who does not have this equipment is not a good union man" (Lee, 1969, p. 96).

To arm the miners, "Old Peg-Leg" Lawrence Dwyer, a member of the International Executive Board of the miners' union, secretly delivered a machine gun and 3,000 rounds of ammunition to the miners. About 6,000 armed miners participated in the march that would lead to the Battle of Blair Mountain (Lee, 1969, p.97).