Congress

All legislative powers are granted to Congress, and creating legislation is the primary function of Congress. In addition to passing laws, Congress oversees the business of the executive branch, monitoring how well agencies are administering the laws and spending federal money. Oversight is an ongoing process, but Congress also may perform special investigations.

As the only branch elected directly by the people, Congress plays a special role in representing the diverse interests of the American people in all actions it takes. Representing and reconciling these interests often takes negotiation and compromise. The people are represented in two ways. Each citizen has two senators who represent them as residents of a state and each has one representative who speaks for them as a resident of a congressional district.

Members of the House of Representatives have been elected directly by the people since its founding. Because of this close connection to the voters, the Constitution gave the House authority to originate all bills to levy taxes and spend government money. The 435 representatives are elected for two-year terms from districts drawn by the state legislatures after each decennial census. States are represented equally in the Senate by two senators. The 100 senators are elected for six-year terms, with one-third of the Senate elected every second year. The longer Senate terms were meant to insulate senators from sudden shifts in public opinion, and states’ equal representation was intended to protect the smaller states. The Senate has the sole power to confirm the President’s nominations and to ratify treaties. Before the adoption of the 17th Amendment in 1913, state legislatures elected the senators. In 1914, all senatorial elections were conducted by popular vote.

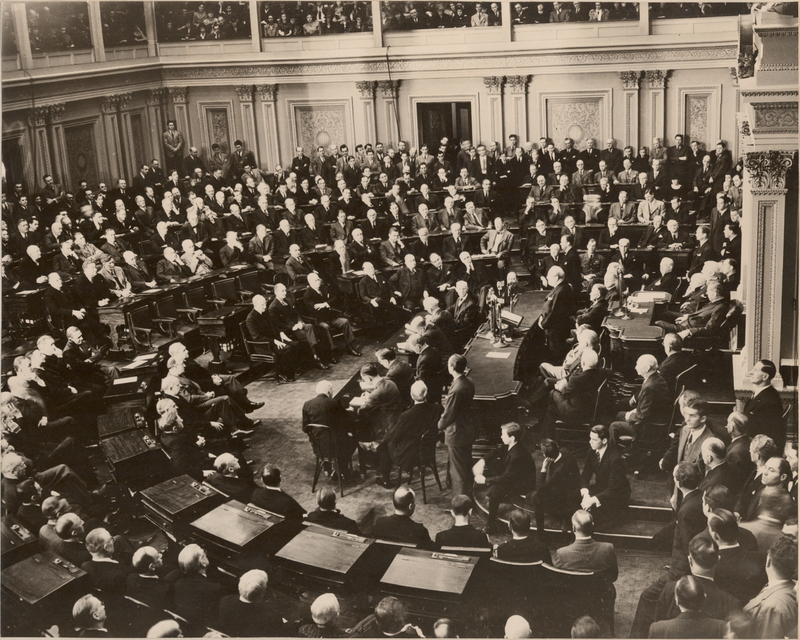

The Oath

At the beginning of each new Congress, the entire House of Representatives and one-third of the Senate takes the oath of office. The Constitution does not prescribe an oath for members of Congress beyond supporting the Constitution, and the First Congress created the simple oath: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States.” At the outbreak of the Civil War, Congress enacted legislation supporting an expanded oath to support the Union, and in ensuing years, the “Ironclad Test Oath” became more stringent to prevent prewar southern leaders from returning to positions of power.

In 1884, lawmakers relaxed the Test Oath, leaving the oath of today intact: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God.”