Section I

“Frontier settlement made significant changes to the mountain environment, but there were more changes yet to come.”

Donald Edward Davis, historian | Where There are Mountains: An Environmental History of the Southern Appalachians

Before white settlement of the Allegheny Highlands, indigenous tribes used forest resources as part of their farming, hunting, and gathering practices. When Euro-American settlers claimed the region, they relied on a frontier lifestyle that blended their own homesteading skills with strategies of forest use adopted from native people. These settlers viewed the region as foreboding and untamed, a longstanding perception of forest wilderness passed down by their European ancestors.

Though unfamiliar and treacherous, the Allegheny Highlands were a place of opportunity for those seeking economic independence. To sustain their families, homesteaders turned dense forests into fields and pastures, but they also left large plots of their woodlands uncultivated. During land rotation cycles, farmers let some fields revert to forest cover, which restored fertility of the soil and eventually brought new growth back to the land. The ancient forests also provided foraging grounds for livestock and wild game that fed on the mast of hickory, chestnut, and oak trees.

Early white settlers also logged the mountainsides—but only as needed to meet local demand. During farming’s off-season, families harvested timber both to supplement their incomes and to build homes and community buildings.

Through this selective use of the forest, farmers created an environment that could sustain themselves and future generations without wholesale destruction of the woodlands. Despite nearly a hundred years of settlement and small-scale clearing, large tracts of virgin forests still stood when the timber boom hit in the 1880s.

Early, non-mechanized methods of cutting timber slowed the removal of the virgin forests. A cutting crew typically consisted of about five men who 1) notched the trees to direct their fall, 2) cut the trees with a crosscut saw, 3) marked the fallen trees into sixteen-foot log lengths, 4) removed limbs, knots, and bark from the cut tree trunks, and 5) sawed the tree trunks into logs. Using horses specially trained for the work, teamsters then pulled the logs to a nearby mill or water route.

To reduce friction while pulling logs behind horses, workers sometimes placed wooden skids along the ground. This practice gave rise to expressions such as “greasing the skids” and “on the skids.” Teamsters dragged logs to the summit of ridges where loggers then rolled—or "ballhooted"—them down cleared paths into waterways.

After the sash saw, the steam-powered circular saw was the next major advancement in milling technology. Since hauling timber long distances by wagon was inefficient, mill operators built stationary circular sawmills with high production capacities along water routes. Some smaller mills, like the one shown here, utilized a steam engine on wheels, making them portable from one logging site to the next.

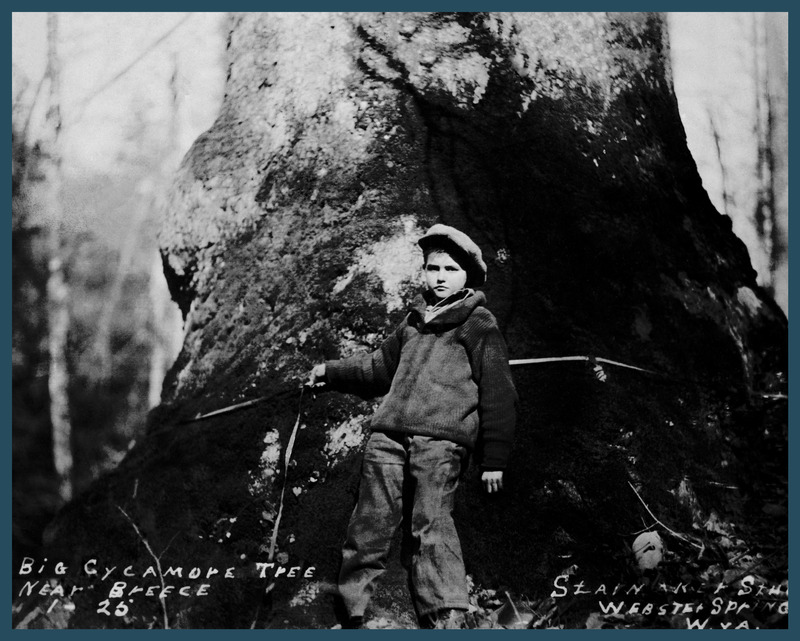

A wide variety of tree species dotted the Allegheny Highlands in the days before widespread timber production—including white pine, spruce, hickory, locust, walnut, cherry, chestnut, and sycamore.

Unlike forests in other parts of the United States, central Appalachia was home to more hardwoods than softwoods. Though hardwood byproducts fetched higher prices than softwoods, the hardwoods were more difficult and expensive to cut, transport, and mill. Therefore, loggers harvested the region’s softwoods first, leaving the hardwoods nearly untouched until the introduction of railroads and heavy equipment allowed for their removal.