Section I - Community

“Where the skies are blue, and the heart is true, I love my mountain home”

“My Mountain Home”

In the pre-industrial Allegheny Highlands, communities shared the use of the land. In addition to farming, mountain residents sold the pelts of animals trapped during winter, floated logs downriver in springtime, and gathered and traded ginseng in the summer. As stated by Burl Hammons, a member of the musical, mountain-living Hammons family, life in the wilderness was “no play job.”

Verses from the song “West Virginia Farmer” reflect the diligence and determination with which locals met the challenges of living off the land:

Oh, the West Virginia hills,With their many rocks and rills,Where the farmer has to scratch away,To see his gran’ry filled.In the early days of spring,To his clearing he must cling,And never think of pleasure-time or any such a thing,He must chop and split and burn,And make every crook and turn,To see his patch of ground a crop of gray.Work away, work away,In the hot and sultry day,In the hot and sultry evening work away,And when the day is done,At the setting of the sun,He can feed his horse a little bit of hay.“West Virginia Farmer”Collected by Patrick Ward Gainer from Nicholas County

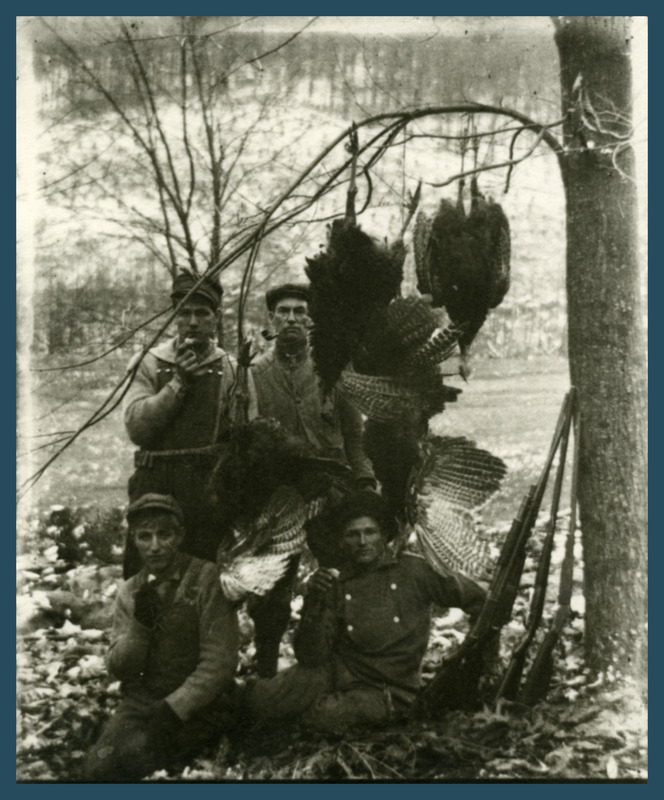

Wild game has long been a staple food in West Virginia households. During and after the timber boom, game animals—like wild turkeys that depended on a healthy supply of acorns and chestnuts—became scarcer, as logging companies clear cut large swaths of forest.

In eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Appalachia, extended family networks and shared resources formed the foundation of social and economic relationships. Communities in the Allegheny Highlands were built upon strong kinship ties that often kept families in the same place for generations. Valuing independence within a secure community over personal wealth, elders encouraged young men to “Stay on the Farm, Boys:”

The farm is surest and safest,Though the profits come in rather slow,You’re free as air of the mountain,And the monarch of all you survey.Then stay on the farm a while longer,Though the profits come in rather slow,Remember you’ve nothing to risk boys,Don’t be in a hurry to go.“Stay on the Farm, Boys”From the journal of Mahala Chapman Mace Gregory, Linor, WV.

Mahala Chapman Mace Gregory, who lived near the Pocahontas-Randolph county line in the mid- to late 1800s kept a journal of song lyrics that she learned in her youth. In addition to this song about a changing national economy, Gregory transcribed many others that influenced her identity as a West Virginian, including songs about immigration, railroads, and logging. Gregory’s documentation of these lyrics confirm that issues surrounding industrialization captured the thoughts of even young girls growing up in rural mountain counties.

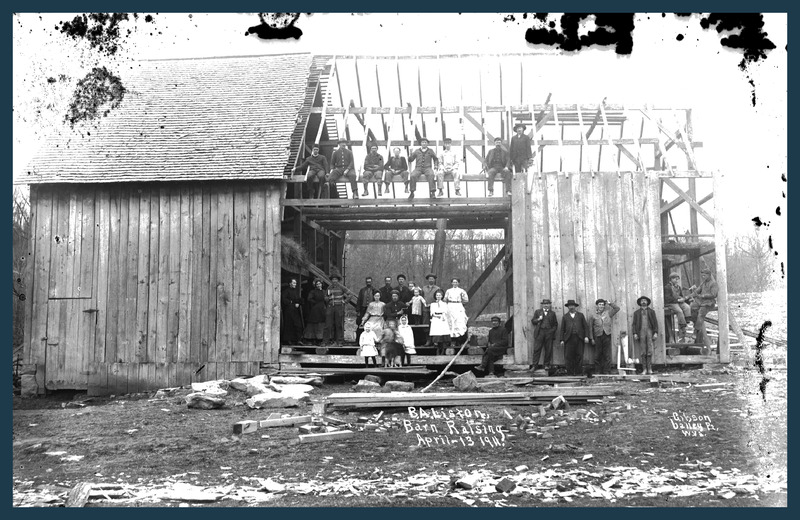

Work and community went hand-in-hand in the era that preceded industrial logging, with extended kinship networks and community members sharing in heavier tasks like barn-building. At these social events, music and dance were often the reward for a day’s hard work. In the evenings, fiddlers stayed busy as families joined together to celebrate work through song.

Despite the hard work that came with mountain life, folks celebrated the beauty and freedom of the Allegheny Highlands. The song “My Mountain Home” conveys the settlers’ appreciation of their natural surroundings:

I love my mountain home,Where wild birds love to roam,Where the cypress-vine, and the whispering pine,Adorn each granite dome.I love my mountain home,I love my mountain home,Where the skies are blue, and the heart is true,I love my mountain home.“My Mountain Home”From the journal of Mahala Chapman Mace Gregory, Linor, WV.