Conclusion

“History tells us how to avoid the mistakes of the past, but it also teaches us that fundamental value change is possible … we need only to look at some of our cultural stories for alternative traditions.”

Ronald D. Eller, historian | Uneven Ground: Appalachia Since 1945

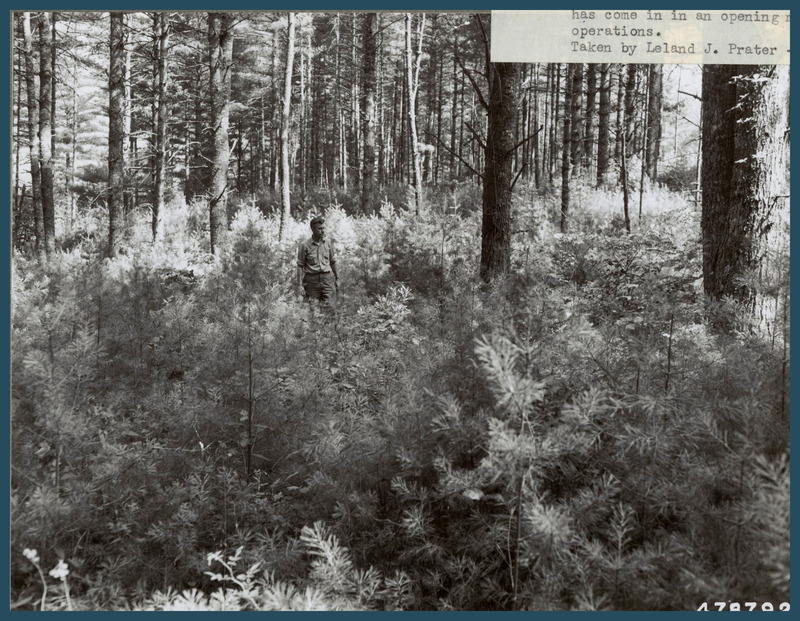

Although the timber boom ended nearly one hundred years ago, the era of industrial logging is far from over. In the twelve-county region known as the West Virginia Hardwood Alliance Zone, nearly 400 companies produce and process wood products. The West Virginia Division of Forestry and the U.S Forest Service work with these companies to ensure that the state’s forest resources contribute to the economy in a sustainable way.

Despite government emphasis on timber management, today’s forests hardly resemble those of early nineteenth-century West Virginia. The mountains have shown great resiliency, but they will never regain the ecological complexity they once had.

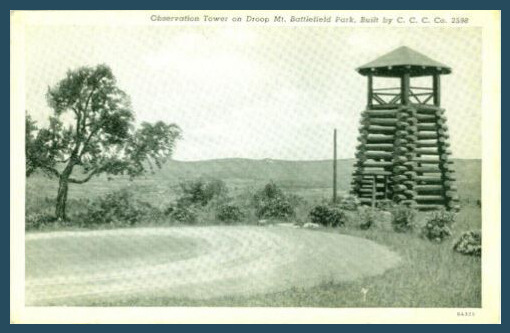

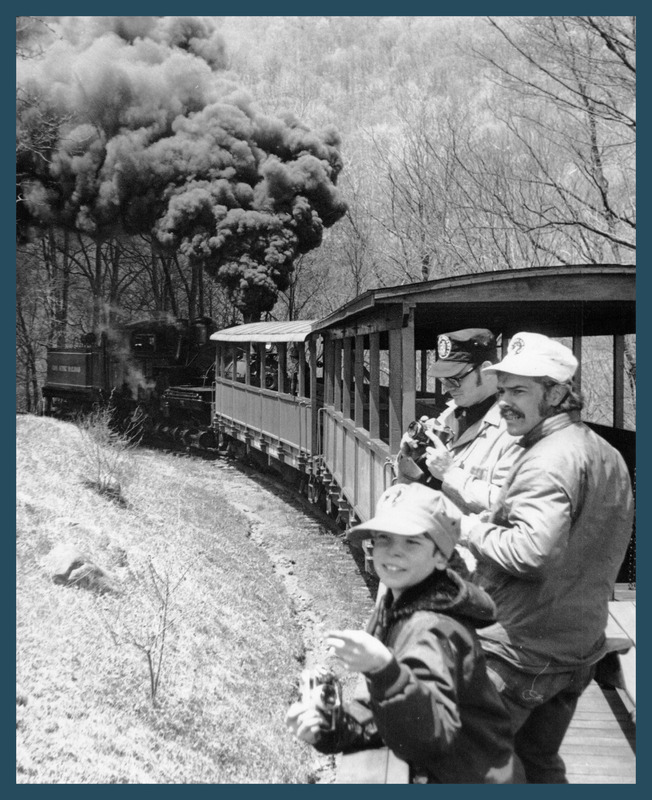

Like the forests, the timber towns that sprang up to support the logging industry have changed shape. Most have disappeared entirely—but the town of Cass is an exception. A grassroots movement to preserve Cass—spearheaded by railroad enthusiasts and other stakeholders—persuaded the state legislature to make the former company town part of West Virginia’s state park system. In 1963, the Cass Scenic Railroad State Park opened to the public, offering visitors a glimpse into the heyday of railroad logging.

Today, state parks, heritage sites, and leisure attractions help create jobs and support local economies in the Allegheny Highlands. With proactive support from state and county governments, the region consistently attracts visitors with its opportunities for recreation, leisure, and heritage-based tourism. Tourism cannot undo the long-term damage caused by industrial extraction of the state’s natural resource wealth, but it helps sustain local communities and preserve cultural traditions in West Virginia’s logging counties.

As stated by historian Ronald D. Eller in his book Uneven Ground, “History tells us how to avoid the mistakes of the past, but it also teaches us that fundamental value change is possible … we need only to look at some of our cultural stories for alternative traditions.” By continuing to examine and invest in our cultural stories—as expressed through the music and traditions of West Virginians—we can further explore the deep roots of our region’s struggles and inspire new initiatives for growth and change.

“Values in old-time music will gradually change in accordance with the values of those of who play it, as they have always done.”

Gerry Milnes | Play of a Fiddle: Traditional Dance, Music, and Folklore in West Virginia

Much of the music once heard in West Virginia’s timber camps has faded into the past—lost in the process of outmigration and the decline of oral transmission of song. Fortunately, folk music in the mountains remains vibrant and diverse, and musical traditions have evolved beyond performance to include educational and preservation projects across the state.

In West Virginia, opportunities to study Appalachian music in its native environment—with the people of the region—are thriving. Colleges and universities have recognized the importance of preserving the legacy of local music and culture, resulting in programs like the Appalachian Music minor field at West Virginia University and Glenville State College’s Pioneer Stage Bluegrass Music Education Center. Since 1973, the Augusta Heritage Center of Davis & Elkins College has offered instruction in a variety of folk arts and heritage preservation fields, including song collection, oral history projects, and community-based performances.

Festivals, like Pickin’ at Parsons and the Appalachian String Band Festival, provide a chance for musicians and lovers of Appalachian music to gather, learn, and jam with each other. In Pocahontas County, the Allegheny Echoes program offers instrumental and vocal instruction in old-time music and conducts workshops on creative writing, songwriting, and performance. By bringing together regional resources and talented musicians, these programs continue the preservation and celebration of Mountain State music.

Until about 1940, the national forests were largely allowed to regenerate through either natural regrowth or replantation programs. However, once new trees grew large enough for harvesting, the Monongahela National Forest contracted plots of land out to timber companies.

Softwoods—like pine and spruce—have a wide variety of uses and grow faster than hardwoods, making them highly marketable. Therefore, forest management practices are often biased towards softwood regeneration.

In the 1990s, as these second growth stands were cut once again, pines returned in even greater numbers, further reducing the number of hardwood species and the native diversity of the Appalachian forests.

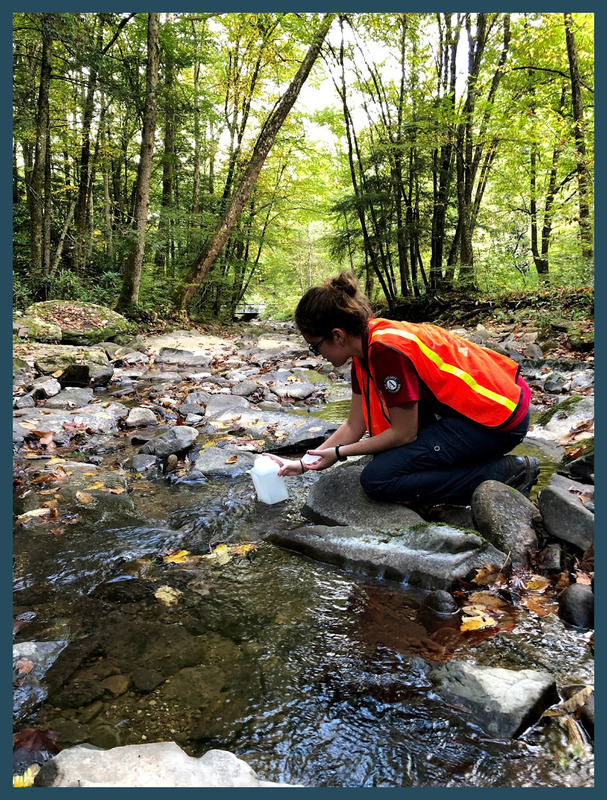

With the overall theme of forest heritage, the Appalachian Forest National Heritage Area (AFNHA) works with partners in eighteen different counties to explore and enhance the relationship between the forested mountains and the people who live there. The work of AFNHA focuses on conservation and forestry, as well as cultural heritage, tourism, and community development. Other organizations, such as the Pocahontas County Convention and Visitors Bureau, also work to promote the benefits of tourism and cultural heritage-based economic activity and to market West Virginia’s timbering counties a destination for leisure and group travel.

With the first public excursion on the Cass Scenic Railroad in 1963, West Virginia took a risk that this tourism venture could help boost the state’s economy, while also preserving the historical significance of the town. Today, many West Virginians view Cass’s legacy as a tourism site, rather than a lumber town.

On the right, a group of former loggers known as the “Cass Symphony” entertains an audience with folk and logging camp tunes at Cass Scenic Railroad State Park.

Since its beginnings in 1973, the Augusta Heritage Center of Davis & Elkins College has promoted and nurtured the traditional music, dance, crafts, food ways, and folklore of West Virginia and beyond. Reaching thousands of people annually, Augusta offers educational workshops, apprenticeship programs, concerts, dances, festivals, and more. Augusta participants—ranging from novice practitioners to professional artists—come from nearly every state and several countries.