Introduction - Part II

“Come all you hicks and lumbermen, Come listen unto me”

"Joker Jess"

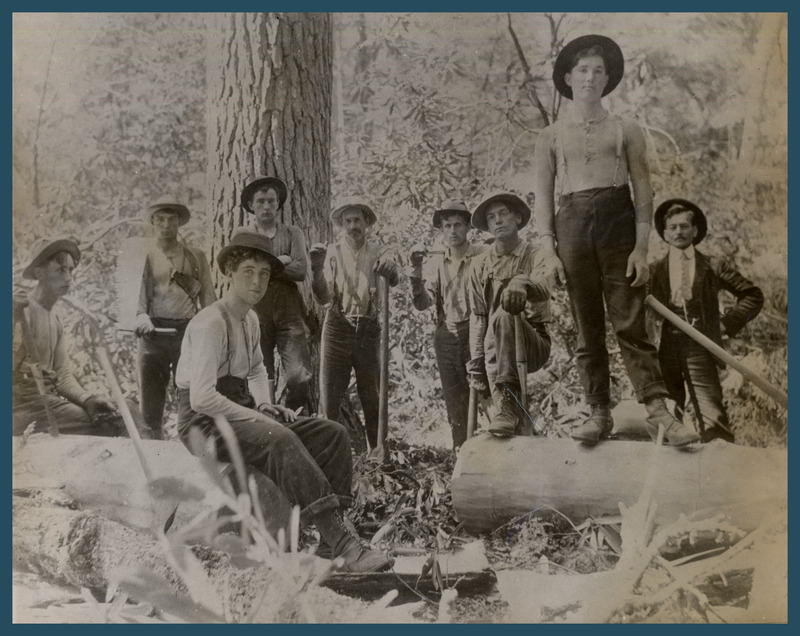

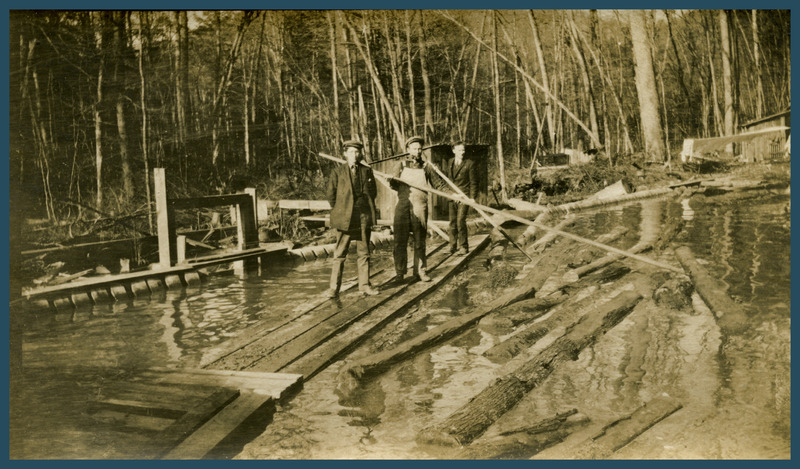

In timber towns and logging camps, loggers wrote and performed music about their work and lives, with some songs originating in West Virginia and others introduced from distant locales. Many of these tunes entered the repertoires of West Virginia’s folk musicians, reflecting the influence of the timber industry on patterns of cultural exchange in the state’s logging counties.

Performed by the legendary Hammons family of storytellers and self-taught musicians, the song “Joker Jess” reflects themes—such as danger, camaraderie, and virtue—that resonated with both migrant loggers and native-born mountaineers. The lyrics tell of a lumber crew that worked hastily and carelessly, causing a falling tree to crush a fellow logger:

Come all you hicks and lumbermen,Come listen unto me,A story I will tell you of,A logger's treachery.In the thirty first day of last September,In the days of '85,We left our camps with merry hearts,And spirits all alive.But little thoughts for Joker Jess,That sent that [spurgin’] tree,We found that we had lost in him,A noble-hearted friend.Too quick, too quick his comrades was,That sent the [spurgin’] tree,That crushed his body to the earth,And set his spirit free.So quick lie round his comrades stood,While over his form did bend,We found that we had lost in him,A noble-hearted friend."Joker Jess"Collected by Dwight Diller from Maggie Hammons in Pocahontas County

According to Maggie Hammons, Joker Jess was a West Virginia logger whose death on Cheat Mountain prompted local lumbermen to compose this song. “Joker Jess” follows the “come all ye” style of logging songs from New England, illustrating the transfer of musical styles from one region to another. Maggie and her brother Burl Hammons likely learned “Joker Jess” from family members with ties to the timber industry. Their grandfather Jesse made money by floating logs downriver in the days before railroads and steam skidders. Decades later, an equipment operator named Nathan Parker found timber work in West Virginia, where he met and married Maggie Hammons.

The influence of the Hammons family on West Virginia folk life spans generations. However, wide recognition of their songs, stories, and traditions did not come until the 1970s when local musician Dwight Diller became closely acquainted with the Hammonses. Diller learned their music, practiced their traditions, and studied their history. His relationship with the Hammonses triggered interest among other musicians and folklorists, and his field recordings and interviews contributed to a study of the family produced by the Library of Congress in 1973.

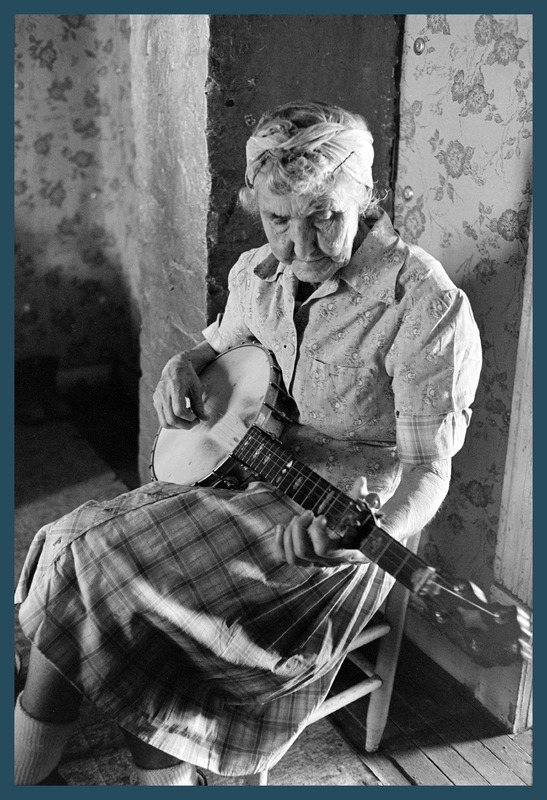

The Hammonses are recognized as central to the preservation of authentic musical styles and culture in the region. Recordings of their music have been released by WVU Press, the Library of Congress, Rounder Records, Dwight Diller, and the Augusta Heritage Center of Davis & Elkins College. Pictured here, Maggie Hammons Parker was a matriarch of the family and one of five Hammonses inducted into the West Virginia Music Hall of Fame in 2020.

Like “Joker Jess,” “The Ballad of Jay Legg” shows an intermingling of cultural influences and suggests universal themes of morality and loss. Reportedly written by an employee of the Cherry River Boom and Lumber Company, the ballad describes the murder of a logger by his wife, Sarah Ann, and her lover:

Come all you brave Elk River boys,Some shocking news to tell,We’ve lost one of our Elk River boys,The one we loved so well.He started out upon the tide,As he often did before,Little did he think ‘twas his last long ride,He never would start no more.There was a man stayed with his wife,Each night while he was gone,They laid a plot to murder him,As soon as he came home.Poor Jay came home one cold winter’s night,Both cold and hungry too,He didn’t have time to sit down and warm,Till a bullet had pierced him through.His gun was loaded and laid away,As the murderers, they did plot,And with his own Winchester gun,He received the fatal shot.There was two men a-passing by,They stepped up to the door,And there they spied poor Jay’s body,A-bleeding on the floor.His little child held up his head,While his life’s blood ebbed away,And to his mother he did say,“What made you kill poor Jay?”“It was an accident,” she said,But she did not seem to care,She thought her own state’s evidence,Would bring her out so clear.He fixed his eyes on his little child,But nothing could he tell,He fixed his dying eyes on them,To bid ‘em his last farewell.Now Jay is dead and laid away,His troubles, they’re all done,His wife is in the Clay County jail,Her troubles are just begun."The Ballad of Jay Legg."Collected by Louis Watson Chappell, from Cyrus Dilly in Braxton County, 1939.

Because the lyrics closely mirror the details of Sarah Ann’s trial, folklorists believe that court proceedings may have inspired the composition of this song. However, a strong tradition of oral transmission also contributed to its evolution. Like nearly all traditional tunes, “The Ballad of Jay Legg” transformed as it passed from one source to another, often overlapping in form and content with a similar song called “Elk River Boys.”

In 1906, sensationalized accounts of the killing of Jay Legg flooded newspapers across West Virginia, characterizing his accused wife as an illiterate, unattractive, and immoral woman. Historical events, human interest stories, and local tragedies—like the Legg murder and trial—became part of the musical traditions of Appalachia. Folklorists working in West Virginia’s logging counties also documented songs about national news events, like the assassination of President Garfield and the sinking of the Titanic.