Introduction - Part III

“Greenbrier River, oh yes, oh yes”

“Greenbrier River”

In the Allegheny Highlands and Greenbrier Valley, waterways were just as essential to life in the mountains as forests and farmland. Known as the “Birthplace of Rivers,” Pocahontas County alone is home to eight separate river systems. Songs like “Three Forks of Cheat” and “Greenbrier River” reflect the historic importance of waterways in the region:

Greenbrier River, oh yes, oh yes,Greenbrier River, oh yes.Greenbrier River, that’ll do, that’ll do,Greenbrier River, that’ll do.“Greenbrier River”Collected by Gerry Milnes from Dena Knicely, Greenbrier County, who learned it as a child from “Black Sam,” a former slave and fiddler.

Throughout the nineteenth century, Appalachia was a major center for raising and trading livestock. In West Virginia, the Greenbrier Valley provided fertile soil for growing feed and ample pastures for raising cattle, hogs, and sheep. Towns along the Greenbrier and other rivers served as agricultural trade hubs—where locals sold livestock to drovers who moved the herds to markets further east. Trade networks like these linked the region to the national economy well before the onset of large-scale, industrialized timbering.

In the Allegheny Highlands and Greenbrier Valley, farming families raised cattle and other animals for profit. While some managed to purchase small agricultural plots of their own, others rented from absentee landowners and local elites.

With the development of railroads and extractive industries in West Virginia, land values rose throughout the state. Middle- and upper-class residents used their local positions of authority to push small farmers off the land through both legal and extralegal tactics. In the process, they lined their own pockets, as well as those of out-of-state corporate interests.

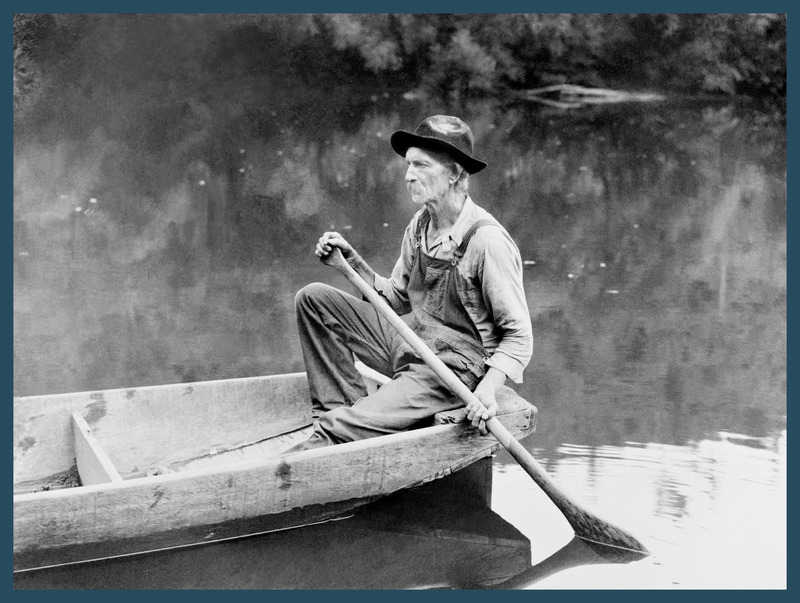

Prior to the arrival of railroads in the Allegheny Highlands, local entrepreneurs used rivers to transport logs from remote mountain valleys to sawmills and market centers. Though many West Virginia waterways were too obstructed, steep, or narrow for rafting timber, others like the Greenbrier River were better suited for log drives.

To move timber to mills or railroad lines, woodsmen either floated loose logs downstream or chained them together to create large rafts. For long log drives, workers often built a bunkhouse and dining hall on top of rafts. Known as arks, these structures followed the mass of logs downriver, while loggers and teamsters traveled down the shoreline to free up timber that lodged against riverbanks. This daring phase of logging history—before railroads penetrated the mountains—gave rise to legends of lumberjack heroes who battled swift currents, giant rocks, and icy waters on long and arduous river drives.

According to local folklore, music also traveled long distances down rivers. In a story told by Braxton County fiddler Ernie Carpenter, his grandfather played fiddle tunes for a young girl one night along the banks of the Elk River. Later, a man who lived thirty-five miles away claimed he could list every tune that the grandfather had played that evening. “They say music will travel a long way on water, you know,” stated Carpenter.

In the late eighteenth century, the Carpenters were one of the first families of European descent to settle the Elk River near the Webster-Braxton county line. Across multiple generations, the family produced some of West Virginia’s most distinguished fiddlers who became known for songs that chronicled the history and folklore of their ancestors.

Though some West Virginia businessmen made enough money from local commerce and agriculture to invest in small-scale industrial ventures, they lacked sufficient capital to build the extensive industrial and transportation networks needed for large-scale timbering. Therefore, the construction of major railroads and massive milling centers relied upon wealthy investors from outside the region with connections to national markets and urban financial centers.

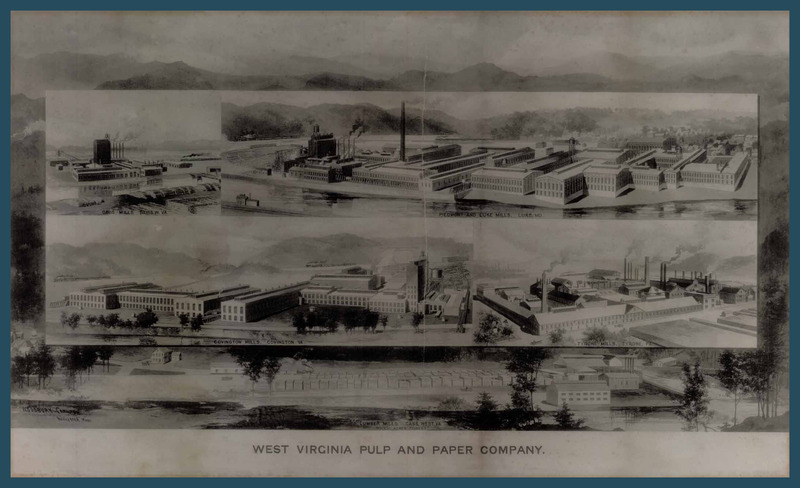

In 1898, the West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company—headed by the Maryland-based Luke Family—planned to build a mill along the Greenbrier River just a few miles from Lewisburg. Realizing that the pulp and paper mill would pollute their water supply, locals opposed its construction, forcing the company to build farther from the virgin forests of the Greenbrier Valley and Allegheny Highlands. Proponents of industrialization characterized these local folks as uninformed and lacking “civic consciousness.” Over the coming years, these industrial boosters increasingly stifled local voices to ensure pro-industry outcomes in disputes of this kind.

Ultimately building their new mill in Covington, Virginia, the Lukes’ thriving, multi-state operations helped convince railroad companies that new rail lines into the Allegheny Highlands were worth the investment.

Once corporate interests recognized the commercial potential of logging the Allegheny Highlands, they bought up large tracts of timber across the region. Often hiring local crews to drive logs downstream, logging companies initially relied on waterways to harvest timber. The most valuable hardwoods and softwoods, however, were inaccessible by water routes alone. Therefore, speculators—both inside and outside West Virginia—held on to their dense, untapped timber tracts until railroads opened the door for full-blown timber extraction.

Whether by river or railway, commercial transportation in the mountains was often daunting and dangerous. Folksongs recorded the legendary exploits of timber and railroad workers who pushed themselves to their limits on grueling log drives and treacherous mountain hauls. “The Wreck on the C&O” describes a railroad accident caused by a landslide near Hinton, Summers County, in 1890. While trying to make up lost time, the train’s engineer took his FFV (“Fast Flying Virginian”) to unsafe speeds—and lost his life as a result:

Along came the old FFV,The fastest on the line,Running over the C&O Road,Twenty minutes behind time.Running into Sewell,

She was quartered on the line,And there received strict orders,Hinton, away behind time.Many a man’s been murdered by the railroad,By the railroad, by the railroad,Many a man’s been murdered by the railroad,And sleeping in his lonesome grave.When she got to Hinton,That engineer was there,George Allen was his name,With bright and golden hair.His fireman, Jack Dickinson,Was standing by his side,Waiting for strict orders,And in his cab did ride.………………………………..He said to his fireman,“Jack, a rock ahead I see,I know that death is waiting there,To grab both you and me.And from the cab you must fly,Your darling life to save,For I want you to be an engineer,When I’m sleeping in my grave.”Down the road she darted,Against the rock she crashed,Upside down his engine turned,And his breast she smashed.His head upon the firebox door,The rolling scenes rolled o’er,“I’m glad I was born an engineer,And died on No. 4.”“The Wreck on the C&O”Collected John Harrington Cox Mrs. Walter M. Parker, Hinton, Summers County, 1915.