Section I - Danger

“With hearts devoid of fear”

“The Jam at Jerry’s Rock”

Though a land of opportunity and natural beauty, the Allegheny Highlands were in many ways a dangerous place. In 1857, writer and illustrator David Hunter Strother described Randolph County, West Virginia, as “so savage and inaccessible that it has rarely been penetrated by the most adventurous. The settlers on its borders speak of it with dread, as an ill-omened region filled with bears, panthers, impassible laurel-brakes, and dangerous precipices.” In the form of song, “Randolph County” warns of the region’s natural hazards:

The hungry bear’s portentous growl,The famished wolf’s unearthly howl,The prowling panther’s keenest yell,These echo from the gloomy dell.The mountains high with grandeur rise,And reach the everlasting skies,The vales between are dark and wild,And streamlets dash or murmur mild.The roaring rivers, rough and wide,Dash down, or pause and softly glide,And oftentimes their rushing waves,Bear dwellers down to watery graves.But still man holds his dwelling there,Defying panther, wolf and bear,But prowling ‘varmits’ plainly tell,This is no place for man to dwell.“Randolph County”Collected by John Harrington Cox from Sallie Evans, Randolph County.

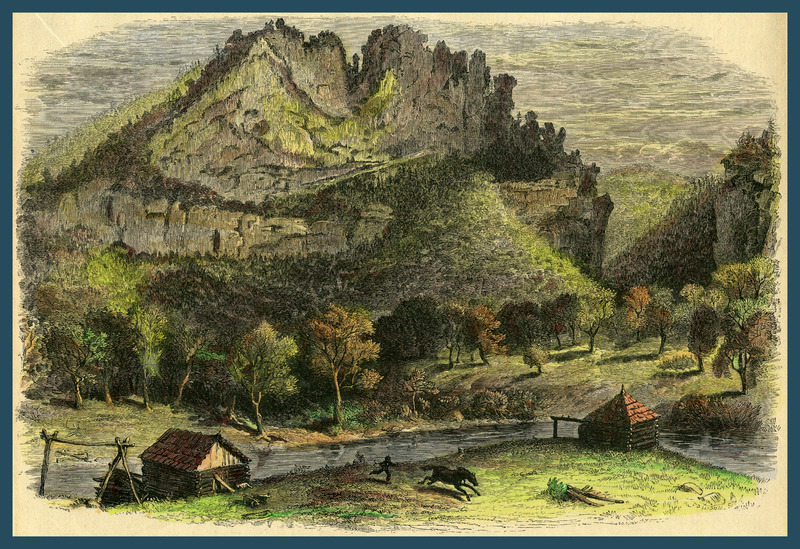

Popular writers and artists of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries often romanticized the ruggedness of the West Virginia hills—as exemplified by this print by David Hunter Strother. While frontier life was certainly challenging, settlers tackled the wilderness by working as family units to survive. Upon meeting a woman from Cheat Mountain, Strother was surprised that “She could cook and keep house…shear a sheep, card and spin the wool, then knit a stocking or weave a gown…She could fish, shoot with a rifle, ride, swim, or skin a bear.” He was also astonished by the woman’s fiddling proficiency that she demonstrated during a schoolhouse dance.

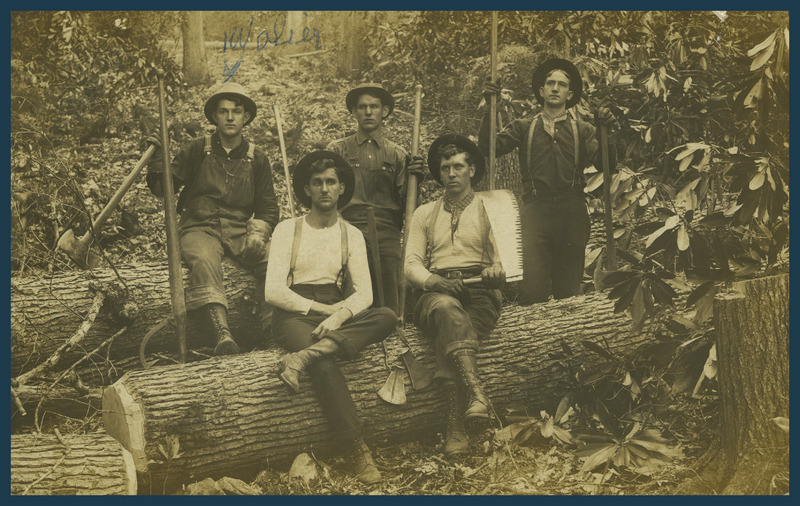

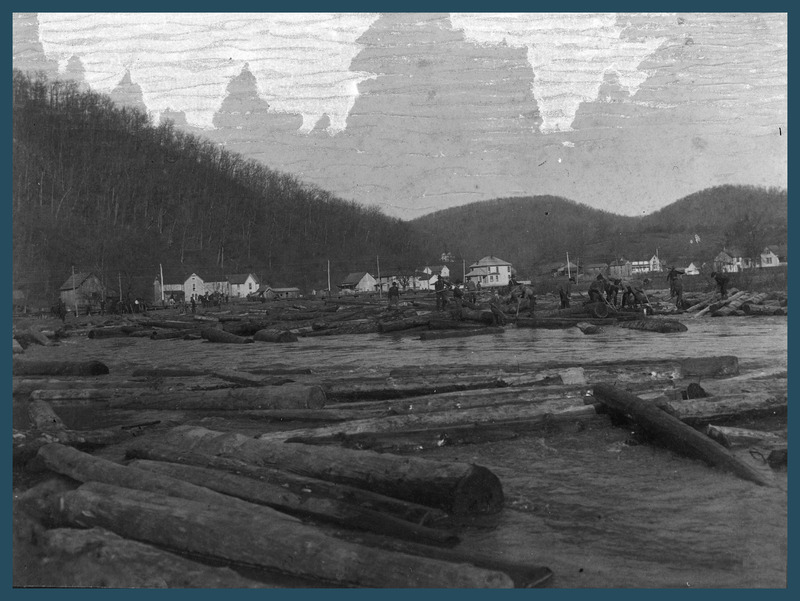

For small-scale logging operations, facing the dangers of the forests was part of the job. From late summer through winter, companies employed local labor crews to cut and haul timber using hand tools and horses. During the spring flood season, men traveled downstream with the logs floating them off to mills and railroad junctions.

One of the riskiest situations that early loggers encountered was the log jam. When floating logs piled up and prevented timber from moving downstream, loggers worked to clear the blockage. One brave team member climbed atop the jam and pried the logs apart using a tool called a peavey. After freeing the logs, the logger who knocked them loose looked for safe footing as quickly as possible. Those who survived this daring task were lauded as heroes, while those who died were memorialized for their bravery.

It was on a Sunday morning,In the springtime of the year,

Our logs they piled up mountain high,We could keep them clear.But our boss, he cried, “Turn out, turn out,With a courage void of fear,We’ll break the jam on Jerry’s Rock,And for Saginaw town we’ll steer.”These words were scarcely spoken,Till the jam did break and go,And carried away those six brave lads,And their foreman, Young Monroe.“The Jam at Jerry’s Rock”Collected by Patrick Gainer from Patrick Starcher, Bolair, Webster County.

Reflecting a trend in which songs became “localized” as they spread from place to place, the titles and lyrics of timber tunes often changed as loggers moved from one camp to another and took favorite songs with them. Canadian versions of this song make reference to floating log rafts across the Great Lakes, while other adaptations mention driving timber down riverways. In addition to “Jerry’s Rock,” folklorists have identified versions of the song titled “Gary’s Rock,” “Hughey’s Rock,” and “Jack Monroe.”

Folklorists collected multiple versions of “The Jam at Jerry’s Rock” in West Virginia, including one version learned in a lumber camp in Nicholas County and another described as “a familiar song among rivermen.”

“I understand that this ballad originated in Northern lumber camps…and was composed to be sung in contests of ballad singing, which was a popular pastime among lumbermen of northern New York. Each ‘shanty’ had its particular song, commemorating incidents of the logging camps or the virtue of the ‘bosses’ of their respective camps.”

John Adkins, Lincoln County. As quoted in Folk-songs of the South by John Harrington Cox

These wood hicks are shown wearing leather boots with spiked soles known as “corks” or “caulks” to help maintain traction on slippery logs. Serious injuries and even death were common occurrences on logging jobs, and few safety measures existed to protect loggers from occupational hazards. Although some large timber operations hired a company doctor, the workers paid monthly fees for his medical services yet still received infrequent treatment for injuries and illness.

After cutting tree trunks into logs, teamsters used oxen, horses, or mules to “skid” the timber downhill. When the slope was steep enough, loggers sometimes split logs in half to form a V-shaped trough known as a chute. They placed the split logs end-to-end, poured water on them until it froze, and then skidded logs down the chute and off the hillsides. While this process increased efficiency in moving timber downhill, the rapidly sliding logs put men and horses at risk.