Section II - Community

“On the banks of a lonely river, Ten thousand miles away”

“The Lone Italian Mother”

The era of industrial logging brought new people, new ideas, and new values to the mountains. Residents were forced to confront changing ideas surrounding labor practices, land use, and social relationships.

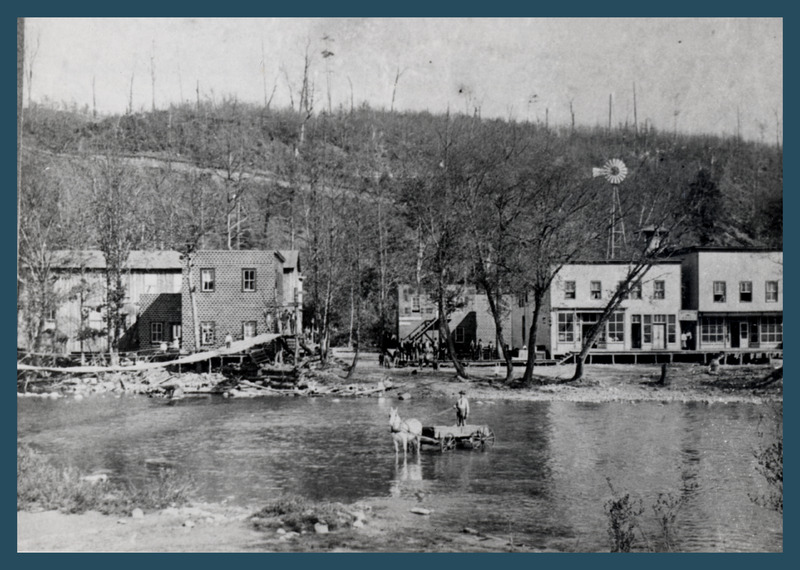

To maximize timber extraction from the forests, companies hired wage workers from across North America, including black men from the South, to supplement the local labor force. Logging and railroad work also attracted immigrants from Italy and other parts of Europe to the Allegheny Highlands and Greenbrier Valley. Despite segregated work crews and bunk houses, diversity in logging camps brought new cultural complexities to the region.

Adversities and animosities that accompanied population shifts in the region could be heard in the music of both transient timber workers and lifelong mountaineers. Through song, workers expressed the thoughts that weighed on their minds—like memories of home and expectations for fair pay and treatment:

On the banks of a lonely river,Ten thousand miles away,I have an aged mother,Whose hair is turning gray.Then blame me not for weeping,Oh! blame me not I pray,For the sake of a dear old mother,Ten thousand miles away.“The Lone Italian Mother”From the journal of Mahala Chapman Mace Gregory, Linor, WV.

Census records from Pocahontas County during the timber boom document the influx of workers from outside the state. In 1870 and 1880, the area now known as Green Bank was comprised almost exclusively of West Virginia- and Virginia-born families. The 1900 census, however, shows residents born in sixteen different states. Among working men in the district, one-third (or roughly two hundred) were foreign born. More than one hundred Italian railroad laborers were reported in 1900, along with fifty-four Greek and sixteen Slovenian workers.

The people around here, they don’t like meThe people around here, they don’t like meThe people around here, they don’t like meBut I don’t care, babe, I don’t careForty-four days, make forty-four dollars,Forty-four days, make forty-four dollars,Forty-four days, make forty-four dollars,All in gold, babe, all in gold.“Yew Pine Mountains”Collected by Patrick Ward Gainer from H.V. Townsend, Gilmer County

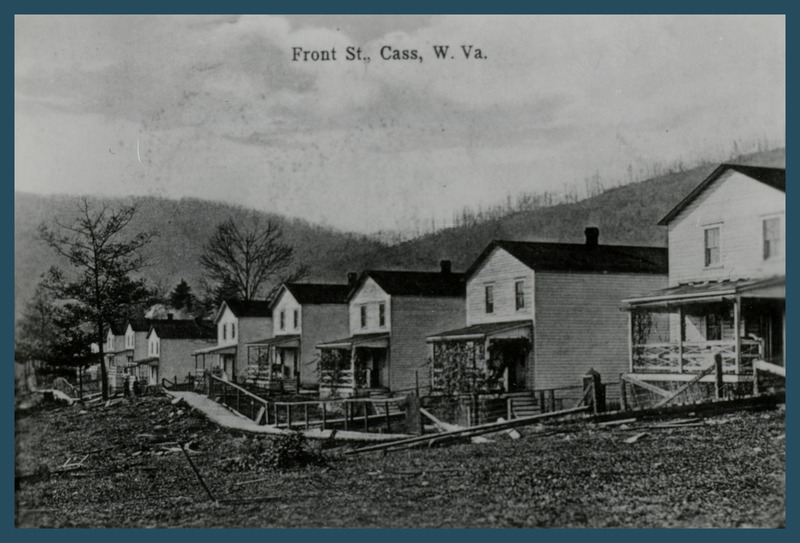

Philip Bagdon, author and member of the Mountain State Railroad and Logging Historical Association, conducted extensive research on lumber towns and logging railroads in West Virginia. In his research notes, he recorded that Italian workers in Cass, Pocahontas County, demanded payment in gold, rather than U.S. currency. Regarding the Italian loggers, Bagdon noted that “local people were opposed to them.”

To lay the tracks for logging railroads, companies hired large crews of unskilled workers—including black laborers and Greek, Italian, and Austrian immigrants—who endured long hours, grueling labor, and harsh conditions for around a dollar a day. Some companies required these workers to wear metal tags with identification numbers. The numbers, not their names, served to identify the men on company payrolls. In some cases, men were buried in unmarked graves with only their identification tags to mark their final resting place.

To attract unskilled laborers, timber companies sometimes advanced food, supplies, or transportation costs to workers before their first paycheck. In some cases, this practice led to serious legal and human rights abuses by companies who held foreign and black workers against their will until they paid back the cost of the advances.

Music historian Erynn Marshall has noted that artistic exchange was a common practice in West Virginia, arguing that most musicians were receptive to the musical styles and performances of different ethnic groups. According to folklorist Gerry Milnes, this embrace of music from other cultures resulted in mountain music with strong connections to a place rather than to an ethnicity.

As workers and their families transitioned to a new cultural environment, music also served as a tool of moral instruction. Some lyrics cautioned women against courting transient workers—who were unlikely to plant permanent roots in the area. In “One Morning in May,” a couple breaks from social norms by wandering unchaperoned in the hills, rather than observing traditional courtship practices. The song notes the musical skills of the logger, while references to his immigrant status, dishonesty, and transience reflected a fear of outsiders:

One morning, two mornings, three mornings in May,I spied a fair couple a running away,

One was a logger, a logger so brave,

The other was a lady, a lady so gay.Oh they hadn’t been there but a moment or two,

‘Til out of the basket a fiddle he drew,He played her a tune ‘til the cold valleys did ring,

Hark, hark, said the lady how the loggers can sing.“Oh now,” says the lady “won’t you marry me?”

“Oh no,” said the logger “such things can never be!

I’ve a wife in old Arland and children twice three,

Two wives make an army too many for me!”Come all you young ladies take warning from this,

Don’t place your affections on a logger so free."One Morning in May"Collected by Louis Watson Chappell from Clay County.

Like many traditional songs, “One Morning in May” has many lyric and title variations. Its origins can be traced back to seventeenth-century England, when it was called “The Souldier and his Knapsack.” During military conflicts, communities sometimes considered soldiers an outside threat to local stability. Likewise, native mountaineers often viewed transient timber workers in a similar light.

“Logging men demanded the freedom to work when and where they chose, and a very high turnover rate prevailed in the wood camps as men grew tired of one place and left for another….If the foreman took notice of a new man who arrived the night before, he was assigned to a crew; if the foreman ignored him, there was no job to offer, and the man set out for the next camp on foot.”

Ronald L. Lewis, historian |Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880-1920

As logging shifted from a seasonal, local enterprise to a more structured industrial operation, some woodsmen left families and communities behind to pursue full-time timber work. Others, joined by their wives and children, set up family homes in timber towns and logging camps.

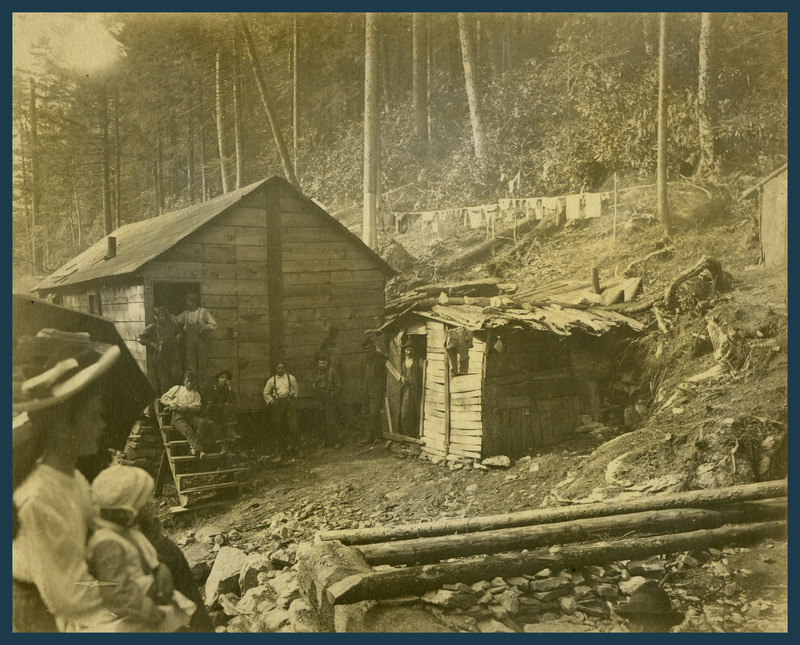

Temporary camps, often built along railroad spurs, accommodated workers who logged the mountainsides for months on end. Made from logs or cheap lumber, camp buildings known as “shanties” were often built on or lifted atop flat railroad cars, making them easily moveable from one work site to the next. Outside West Virginia, loggers themselves were called “shanty boys,” a term commonly used in timber camp songs.

The food served at logging camps was legendary for its quantity and quality. The camp cook received premium pay for working pre-dawn through late-night shifts to feed the hearty appetites of loggers. Assisting the cook were the “cookee” and the “lobby hog” who made half the pay but worked just as hard to prepare food, wash dishes, scrub tables, and perform other grunt work in the dining halls.

Middle- and upper-class elites not only pushed for industrial growth in Appalachia, they also thrust their mainstream morals and social standards upon the mountains. Lyrics of songs collected in early twentieth-century West Virginia reflect the “civilizing” influence of reformers who stereotyped mountain folks as primitive, uneducated, and peculiar.

The song “The Ladies and the Snuff” scorns the unruly, undesirable nature of women who chew tobacco:

All o'er the country, state, or land,When the ladies think themselves so grand,They scarce can get enough to wear,They rub their snuff and curse and swear.And when they go to church in prayer,Their old snuff box is always there,And when the good Lord's prayers are found,The ladies pass the snuff around.Now all young men pray do be wise,If you want to take some good advice,If you want to live a happy life,Don't marry a snuff box for a wife.“The Ladies and the Snuff”Collected by Patrick Ward Gainer.

“My daddy used tobacco and smoked too. And Emmy would find his tobacco, he didn't know it, but he said he knowed she was slipping it out. She'd find his tobacco, and she got to slipping it out and giving it to me.”

Maggie Hammons. As quoted in The Hammons Family: A Study of a West Virginia Family’s Traditions, edited by Carl Fleischhauer and Alan Jabbour.

Not to be confused with a different song called “Greasy String,” the lyrics of “Greasy Coat” profess pride in clean and virtuous living:

I don't drink and I don't smoke,I don't wear no greasy coat.I don't spit and I don't chew,I don't kiss the girls that do.I don't cheat and I don't lie,All you sinners are gonna die.I don't stink and I don't smell,All you sinners can go to hell.“Greasy Coat”Collected by Louis Watson Chappell from Edden Hammons, Webster County, 1947.

“When respectable citizens mobilized to incorporate Cass and to threaten its saloons and whorehouses, these services simply moved across the Greenbrier River to an unincorporated zone, which inevitably became known as ‘Brooklyn’ and the swinging bridge that connected it to Cass as ‘the Brooklyn Bridge.’ Not until a middle-class temperance crusader disguised herself in men’s clothes and gathered evidence that implicated local lawmen were the cribs [brothels] and blind pigs [speakeasies] of Brooklyn closed down.”

John Alexander Williams, historian | Appalachia: A History