Section II - Danger

“A logger’s life is a dreary life”

“A Logger’s Life”

In the era of full-blown industrialized logging, an emphasis on speed and profit often came at the expense of safety. Like many industrial work sites, sawmills were hazardous places, and few regulations existed to protect workers from harm. Mill workers could get caught in moving machinery and lose hands or fingers to saw blades. With the loss of limbs, some workers also lost their and suffered a life of poverty.

When men died on the job, song lyrics captured the sorrow of widowed wives and grieving lovers:

A logger’s life is a dreary life,It robs poor girls of their hearts delight,It causes them to weep and mourn,For the loss of true love never can return.I heard my father call my name,Said “Here’s a letter for you, my Jane,”And the very first words that caught my eye,Your lover boy is bound to die.Straight, straight to the hospital, then I sped,But oh too late, his spirit had fled,God has called him, he’s gone to rest,He calmly sleeps on the Savior’s breast.There’ll be no wars on Canaan’s shore,There will be peace forever more,When God calls me I’ll go with joyAnd will live happy with my logger boy.“A Logger’s Life”Collected by Louis Watson Chappell from Nancy Hammonds, Nicholas County, 1947.

As timbering operations became increasingly mechanized, the use of heavy equipment and more complex machines brought new industrial hazards. Fast-moving gears, blades, belts, and wheels on logging trains and in modernized sawmills caused the loss of many workers’ limbs and lives.

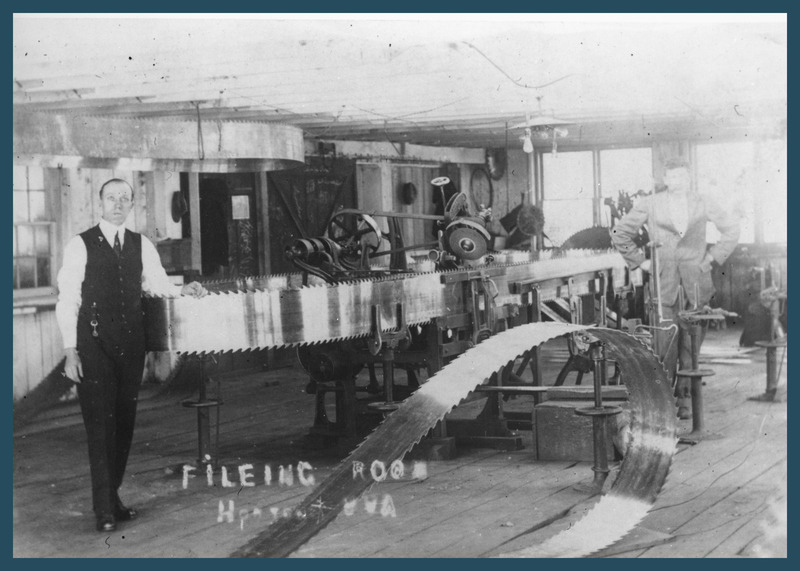

Along with logging railroads, the high-efficiency band saw first appeared in the West Virginia mountains during the late nineteenth century. Band saws could accommodate larger-diameter timber than the circular saw, and they milled logs into lumber faster than any previous invention. Mountains once cloaked in trees soon became “stumptowns.”

Initially powered by steam and later by electricity, the band saw consisted of a belt of saw-edged steel running around large wheels at high speeds. The filer, whose job was to sharpen the saw blades, was one of most skilled and highest paid workers in a lumber mill.

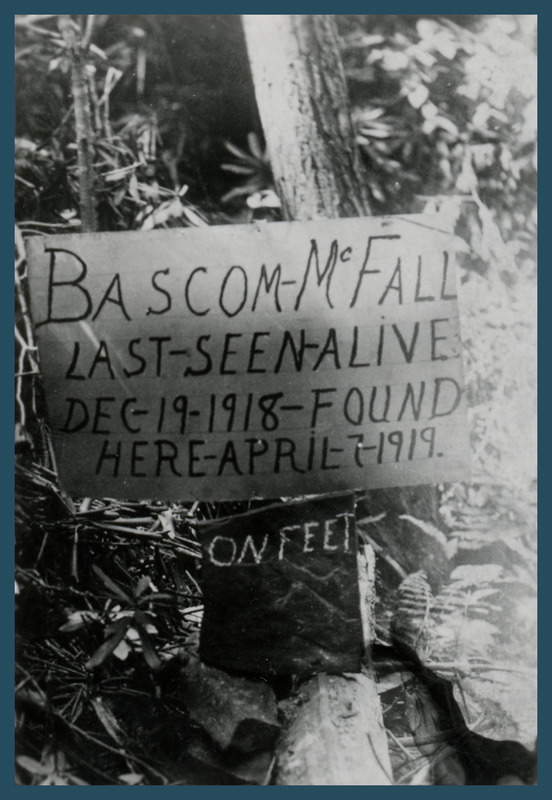

For labor crews on logging trains, the heavy loads, steep grades, and poor tracks on railroad lines made for risky and sometimes lethal work. Accounts of accidents, injuries, and deaths on logging railroads filled newspapers of the day, and stories and songs about runaway trains became part of mountain logging legends.

The brakemen, who jumped from car to car to set the train’s brakes, had a particularly hazardous job. On Cheat Mountain, one brakeman fell between the cars, and the wheels “just cut him up in pieces as big as your hand.”

On steep and muddy hillsides, risks were ever present as well. In 1907, George Lough, who worked for the Bemis Lumber Company in Randolph County, was tightening the cable on a log skidder when it jammed on a stump. The skidder cable snapped and broke Lough’s neck, instantly killing him. A year later, another Bemis employee, Stephen Tallmadge, died when he slipped and fell onto his axe. An eyewitness noted that Tallmadge had been singing “The Johnstown Flood” right before his fall:

On a balmy day in May, when nature held full sway,And the birds sang sweetly in the sky above,A lovely city lay serene in a valley deep and green,Where thousands dwelt in happiness and love.Ah, but soon the scene was changed for just like a thing deranged,A storm came crashing through the quiet town,The wind it raved and shrieked, thunder rolled and lightening streaked,And the rain poured awful torrents down.Then the cry of distress rang from east to the west,And the whole dear country now was plunged in woe,For the thousands burned and drowned in the city of Johnstown,All were lost in that great overflow.“The Johnstown Flood”Collected by Patrick Ward Gainer.

Referring to an 1889 dam collapse in Pennsylvania partly attributed to water runoff down timbered hillsides, “The Johnstown Flood” alludes to industry’s ravaging impact on nature and mankind. Hitting the town at forty miles per hour, the flood killed more than 2,200 people and completely destroyed four square miles of property. Like the rains that fell on Johnstown, the storm of rapid industrialization came down hard on rural hillsides and towns in the Greenbrier Valley and Allegheny Highlands. The destructive effects would be felt for decades.