Section III

“Where trod the logger o’er the deep, the river flows alone, while rolling waves recall the past with sad, regretful tones.”

W.E. “Tweard” Blackhurst, author | Riders of the Flood

By the 1920s, logging in the Allegheny Highlands was on the decline, and much of the landscape had become unrecognizable. Large-scale deforestation contributed to fires, droughts, erosion, and floods that destroyed wildlife habitat and damaged farm fields and pastures.

Conservationists had long been alarmed by the environmental impact of industrial logging on both forests and waterways. As the timber boom reached its peak, they advocated for federal protection of woodlands across the United States. In 1911, Congress passed the Weeks Act, making the federal purchase of land for national forests possible. Nine years later, the government established the Monongahela National Forest in eastern West Virginia.

Even lumber barons welcomed federal land acquisition, capitalizing on the opportunity to profit off their cutover timber tracts. Many farmers in the region, now operating on smaller plots, also opted to sell land to the government, which diminished the viability of agriculture and contributed to outmigration from the region. Locals’ ability to live off communal land was further restricted by government regulations on hunting and fishing. Federal land ownership also limited community and economic development in the region by removing substantial acreage from the local tax base and making land unavailable for other types of enterprise.

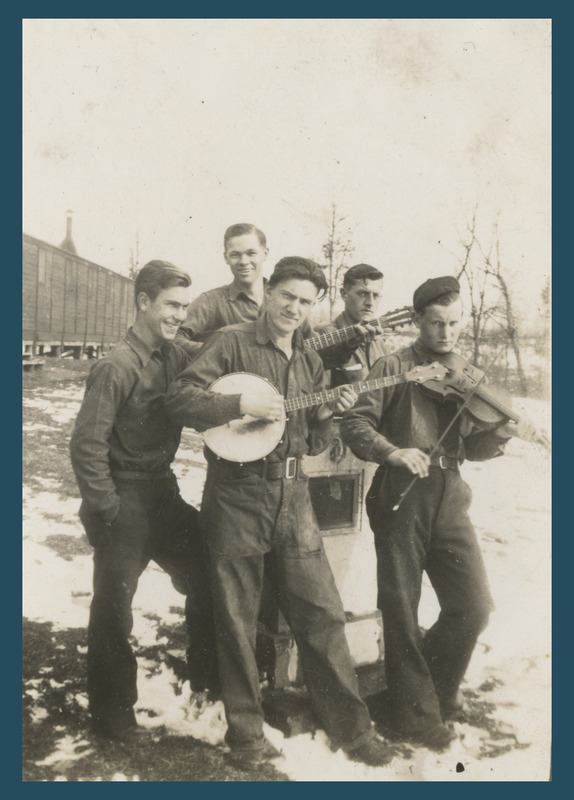

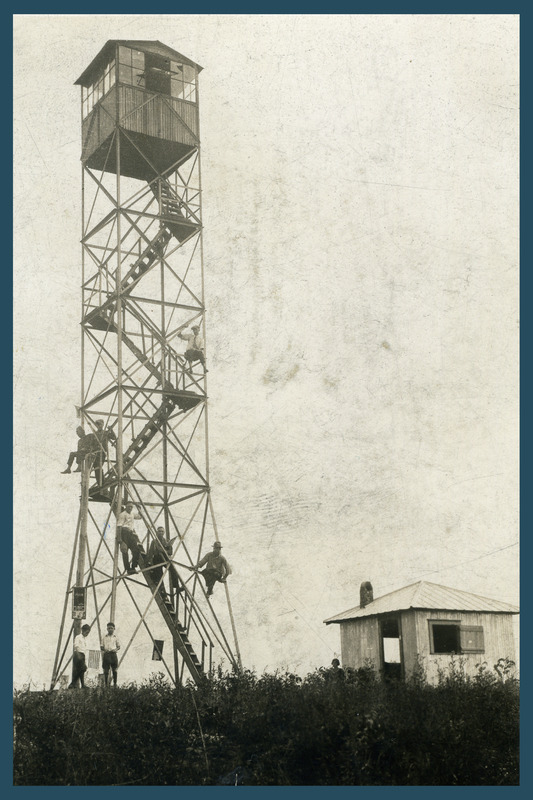

Despite these repercussions on local land use, government conservation efforts benefited the landscape. During the 1930s, the Civilian Conservation Corps planted trees and developed land for recreational purposes. The U.S. Forest Service adopted a program of managed timbering as part of its mission to sustain diverse ecosystems for present and future generations. Amidst growing concerns that the Forest Service was too focused on timbering, Congress passed the Multiple-Use Sustained-Yield Act in 1960, which directed the agency to treat all uses of the national forests—recreation, timber, watershed, wildlife—with equal priority.

The forests began to heal, but the transformative impact of the timber industry would always be felt.

The use of new and more efficient logging equipment—like Shay locomotives and steam-powered skidders—increased the environmental destruction of the timberlands. On remote mountaintops, lumbermen used skidders with overhead cables to drag logs across steep slopes. The skidders destroyed everything in their path, leaving skid trails and gouges that contributed to the erosion of clearcut hillsides.

The West Virginia timber industry reached its peak in 1909, and then entered a long-term decline as new materials—like reinforced concrete—began to replace wood in building construction. Scrambling to stay afloat, timber companies slashed prices, cut labor costs, and ramped up production, which further glutted the lumber market. Having wiped the Allegheny Highlands of its timber, the lumber barons set their sights on forests in the southern and western United States.