Section III - Community

“Lumberjack, it’s time for you to go”

“The Lumberjack”

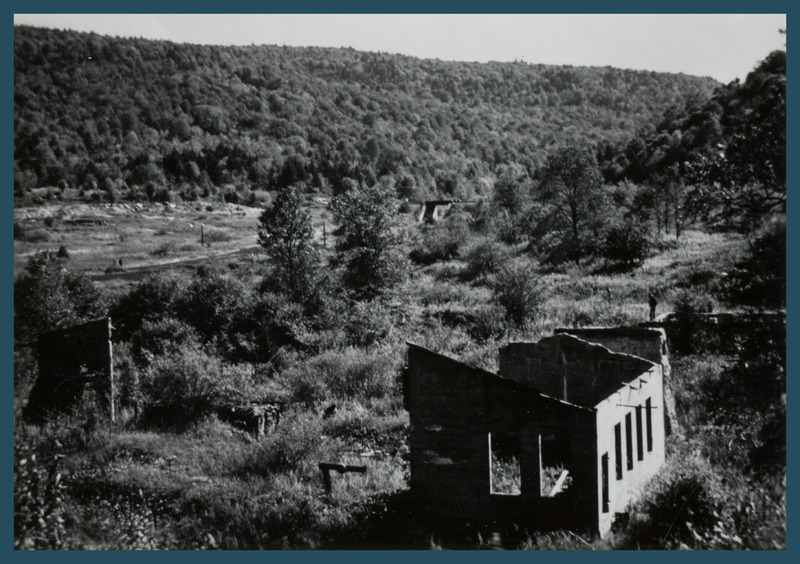

As logging and lumber work declined in the Allegheny Highlands, communities that grew up around the timber camps began to disappear. Without loggers and their paychecks, once-prosperous towns like Spruce in Pocahontas County soon faded from the landscape. Formerly home to 900 residents, a hotel, company store, and a two-room school, the only remnants of Spruce still visible today are a few crumbling foundations and a railroad track.

Oh, the lumberjack is fun till his money is all gone,Then the landlady begins to overcome,With a nasty, glary eye and a face all awry,Sayin’ lumberjack, “It’s time for you to go.”“The Lumberjack”Collected by Louis Watson Chappell from retired loggers, Amos and Sid Hathaway, Nicholas County, 1939

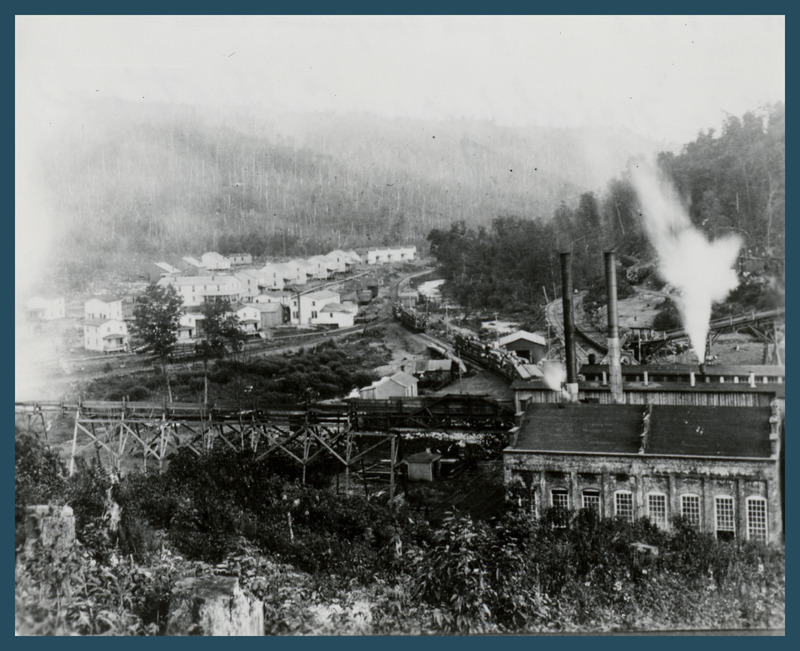

Around 1905, West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company built a rossing (peeling) mill along Shavers Fork of the Cheat River, as well as housing, a company store, and a hotel. At 3,853 feet above sea level, this new community—known as Spruce—was one of the highest elevation towns in the eastern United States.

Accessible by railroad only, Spruce was a vibrant mill town until 1925 when the peeling mill closed due to the declining availability of pulp logs. Today, visitors can hike to the site and witness firsthand how the forest is erasing evidence of industry, with new growth taking hold where buildings once stood.

The prosperous ventures of West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company lasted more than forty years before it sold its operations to Mower Lumber Company in 1943. The town of Cass appeared to be on its last legs after Mower Lumber closed its doors and sold the town—lock, stock, and barrel—to an out-of-state company in 1960. The town’s population plummeted steadily; by 2010, there were only fifty-two residents in Cass. Following this trend, other lumber companies closed, forcing many workers in the region to seek employment outside the timber industry.

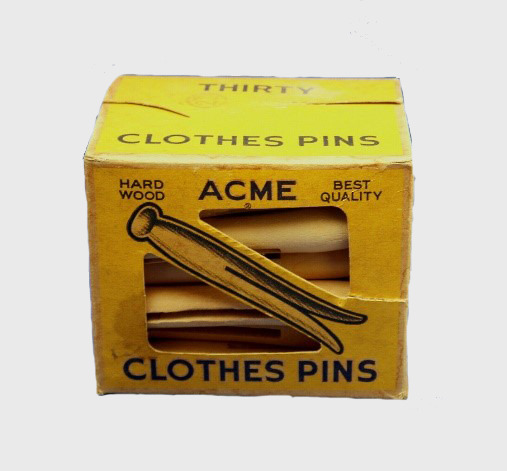

With the town’s name reflecting the timber wealth in the area, Richwood in Nicholas County was home to several wood byproduct factories. While the choicest trees were milled into lumber, lower quality timber ended up at Richwood’s paper mill, handle factory, or clothespin plant. Established by a Pennsylvanian in 1901 and the later sold to the Wallace Corporation, the Dodge Clothespin Factory produced toothpicks, wooden dishes, and paper trays. Its main moneymaker, however, was the clothespin, which it sold under brand names like Acme, Top Fire, and Maid of Honor.

When the timber boom waned during the Great Depression, the Wallace Corporation tried to stay competitive by updating its products—adding a metal spring to its clothespin in the 1930s and later offering a square version. Eventually, plastic clothespins, clothes dryers, and global competition took their toll on the Richwood plant. The Wallace Corporation closed the factory in 1959 and moved its equipment to Sweden, where it paid workers an hourly rate of 28 cents—compared to $1.63 in West Virginia. More than two hundred workers in Rich- wood, about half of whom were women, lost their jobs.

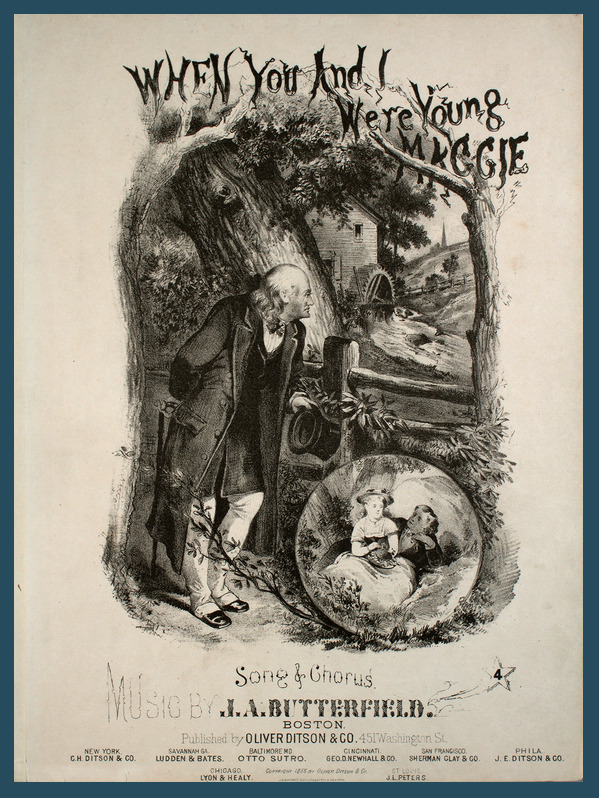

The song “When You and I Were Young Maggie” evokes emotions felt in a changing world—where familiar scenes like the decline of Spruce played out across the region:

I wander’d today to the hill, Maggie,To watch the scene below,The creek and the creaking old mill, Maggie,As we used to long ago.The green grove is gone from the hill, Maggie,Where first the daisies sprung,The creaking old mill is still, Maggie,Since you and I were young.“When You and I Were Young Maggie”Collected by Thomas S. Brown from Dewey Hamrick and Woody Simmons, Randolph County, 1972.

The mention of a mill in this song likely refers to a grist mill. Some mills, however, processed both timber and grain, serving a dual purpose in rural communities.