Section III - Danger

“My hands can't fiddle and my heart's been broke”

“Damned Old Piney Mountains”

In a state that actively promoted the extraction of its natural resources, the timber companies’ wastefulness and disregard for West Virginia’s future went largely unchecked. State lawmakers endorsed policies that favored industrial over subsistence use of the land, failing to protect small farmers and the natural landscape from corporate exploitation and environmental abuse. Furthermore, without funding and guidance at the state level, local municipalities lacked the means to enforce the few, loose conservation laws that were enacted.

While destructive “cut out and get out” methods brought short-term profit to absentee timber barons, average West Virginians bore the costs of industrialized timbering for years and years. The song “Damned Old Piney Mountains” captures some of the hardships and heartaches that former loggers and mill workers likely felt in the post-boom days of timber:

Sit down buddy we'll drink and smoke,Woman don't you weep for me,My hands can't fiddle and my heart's been broke,You damned old piney mountain.Lost my fingers in the Galax mill,Buddy sing a sad old song,And my heart got broke in the yew pine hills,Lordy my time aint' long.I started out to loggin' when I was in my prime,Woman don't you weep for me,Hitchin' up the spruce to the big drag lines,You damned old piney mountain.Where the skidders start a-buckin' as the years come down,Buddy sing a sad old song,Making' God's own thunder on the new-cut ground,Lordy my time ain't long.We was fightin' over nothin' and drinkin' too hard,Woman don't you weep for me,Ridin' up to camp on the flat-wheel car,You damned old piney mountain.Thirty years a-hangin' on the old chain brake,Buddy sing a sad old song,Laid off and paid off in '58,Lordy my time ain't long.And the skidders got sold to a scrap iron yard,Woman don't you weep for me,I moved down Virginia when the times got hard,You damned old piney mountain.Lost my fingers to a steel band saw,Buddy sing a sad old song,Now my fiddle just hangs untuned on the walal,Lordy my time ain't long.And the trees have grown up on the logging road,Woman don't you weep for me,And the wildflowers bloom where the big shays blow,You damned old piney mountain.There's nothin' left for me but to drink and smoke,Buddy sing a sad old song,My hands can't fiddle and my heart's been broke,Lordy my time ain't long. Damned Old Piney Mountains.From a lecture by Gerry Milnes at Augusta Heritage Center, Elkins, 2019, with lyrics from Craig Johnson.

In the mountains of West Virginia, an old-time string musician named Craig Johnson met an elderly man who was once a fiddler and logger. Having lost four fingers while working at a sawmill, the man could no longer play music—and he requested that Johnson play a “sad old song” for him. After playing the song, Craig composed “Damned Old Piney Mountains” to preserve the old man’s story of timbering and tragedy.

Despite documenting the woeful loss of a man’s fingers, fiddling ability, and livelihood at the hands of industrialism, this song shows signs of hopefulness and resilience—with the appearance of forest regrowth and the reclaiming of railroad lines by wildlife.

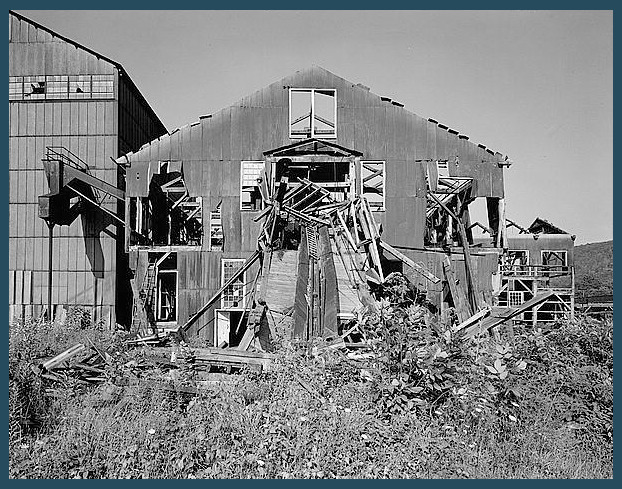

In the early 1900s, two brothers from Pennsylvania—Thomas and John Raine—founded the Meadow River Lumber Company and the “model lumber town” of Rainelle, West Virginia. Unlike absentee owners of other large timber companies, John Raine made Rainelle his permanent home.

With products that ranged from flooring and furniture to coffins and shoe heels, the Raines’ company was the largest hardwood lumber operation in the world during its first decades of operation. The Great Depression and the development of new building materials dealt a huge blow to West Virginia’s timber industry, but Rainelle managed to outlive many of the state’s other lumber towns. When Meadow River eventually closed down in the early 1970s, its mill buildings were demolished and its company homes sold off.

West Virginia’s logging communities were highly gendered spaces, with different expectations for men’s and women’s work and behavior. In the days before industrial timbering, some women and teenage girls participated in logging work by driving supply wagons and occasionally using horses to skid logs. As more and more wood hicks came to West Virginia to find work, women sometimes made money by converting their homes into boardinghouses for single men.

Between 1907 and 1912, a woman named Hannah Gaskill performed bookkeeping at a mill office in Tucker County. In her diary, she described how men at the mill disapproved of her work outside the home, and some even refused to speak to her. Hannah also noted that the men modified their behavior in her presence—avoiding raunchy stories and explicit language.

The hiring of women in lumber company offices became more common over the years—but post-boom layoffs did not discriminate. The closing of Mower Lumber Company in Pocahontas County put nearly everyone in Cass out of work—not only male loggers and millworkers, but also women employed in offices, classrooms, and retail businesses.

In the late nineteenth century, West Virginia lawmakers began to deviate from legal traditions inherited from Virginia’s government. In property rights cases, judges sided with “the captains of industry,” making it nearly impossible for farmers to protect themselves against railroads and timber companies in court. While Virginia law required railroads to fence in their right-of-ways, West Virginia passed legislation “making it unlawful for horses, cattle, etc., to run at large on a railroad right-of-way, and fixing a penalty on the owner if injury to property results therefrom.”

Many West Virginia farmers resented industry and government not only for this assault on their traditional rights and legal standing, but also for economic losses caused by railroads. While business interests enjoyed state tax relief in various forms, farmers faced higher tax burdens as industrialization caused property values in the region to rise. Furthermore, trains brought in cheaper goods that undersold local farmers’ products—dealing another blow to the agricultural economy.

By the end of the timber boom, the culture of the mountains had transformed from one grounded in agriculture and local authority to one that privileged industry and absentee interests. West Virginia’s industrial transition restructured rural communities in ways that aroused local fear of powerful institutions and outsider control.

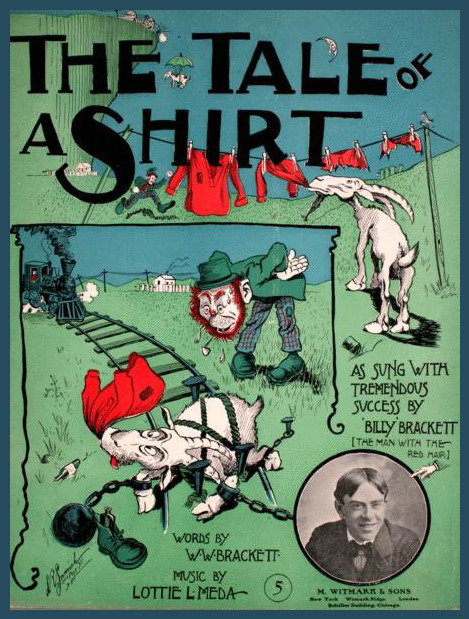

The song “Emery Mack and His Goat” provides a lighthearted take on a more serious theme in the story of West Virginia’s timber boom: the confrontation between industry and agriculture. In a comical twist, the goat gets the better of both the farmer and the train in this story:

Old Emery Mack, a friend of mine,Had three red shirts out on the line,He bought a goat, just for a time,And “Billy” ate those shirts right off the line.Emery kicked and swore,And made things roar,Swore he would have,That goat no more.He caught that goat right by the back,And tied him to the railroad track,But when the train came rolling by,That goat was too sharp to die.He coughed and heaved,With might and main,Coughed up those shirts,Flagged down the train.“Emery Mack and His Goat”Collected by John Harrington Cox from Mr. Fred M. Smith, Glenville, Gilmer County

Commonly sung during children’s games, “play party” songs like this one were included among the folk music performed by Appalachians. Like many other folk tunes, the song made the transition to commercial music—with Fiddlin’ John Carson first recording a version of this “hillbilly hit” in 1923.

Though Appalachians never described their songs as hillbilly music, the recording industry used the term to market songs rooted in southern rural traditions. In the mid-twentieth century, record labels began grouping the hillbilly music genre under the broader category of country music.

In addition to years of devastation to their physical environment, West Virginians also faced damage to their social standing and cultural image. The efforts of outside reformers to “civilize” mountaineers were reinforced by mainstream news and cultural outlets that portrayed rural folks as backward, illiterate people. Images like this sheet music cover for a version of “Emery Mack” depicted the country farmer as poor, foolish, and slovenly, suggesting to the nation that his battles against industrialism were ill-informed and futile. Well beyond the timber boom, these representations continued—and contributed to false stereotypes of Appalachians as responsible for their region’s economic underdevelopment.