Introduction - Part I

"Measuring the significance of the passing of the wilderness lies in a realm beyond historic documentation."

Ronald L. Lewis, historian | Transforming the Appalachian Countryside: Railroads, Deforestation, and Social Change in West Virginia, 1880-1920

Between 1880 and 1930, the timber industry brought lasting, tumultuous changes to life in the West Virginia highlands. The depletion of timber in other parts of the United States coincided with the development of new railroad lines and logging technologies that made mass extraction of the state’s vast, virgin forests possible. Logging companies responded with a push to claim the hardwoods and softwoods of the Allegheny Highlands, launching a frenzied timber boom that left few trees—and few lives—untouched.

Writers and researchers have examined the history of timbering in West Virginia, documenting its impact on politics, the economy, and the natural environment. The perspectives of timber workers and average mountaineers, however, are often missing from the written record, despite their importance in understanding the industry’s significance in the Mountain State. This exhibition explores everyday cultural expressions—such as playing music and singing songs—to uncover the concerns, sentiments, and values of those who lived and worked on the hillsides of the Alleghenies.

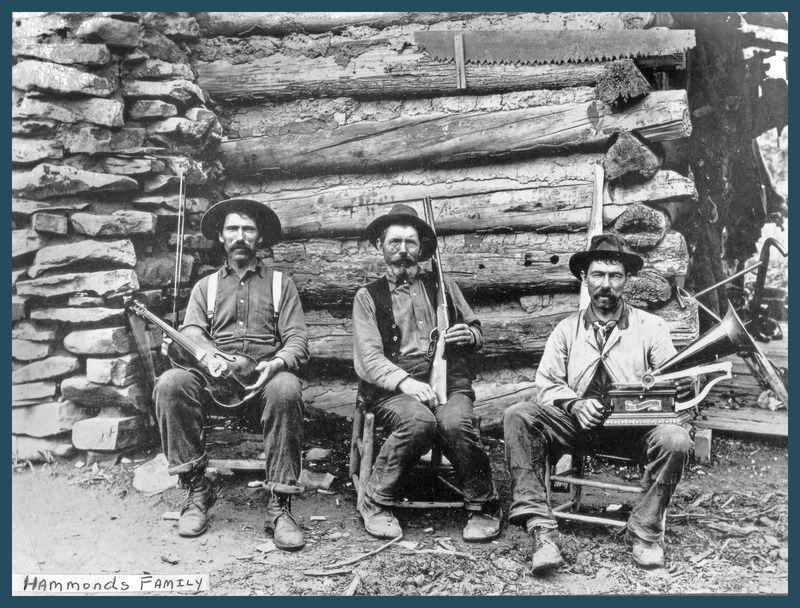

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, music offered a respite from the hard life faced by immigrant workers, transient loggers, and native-born mountaineers in West Virginia’s timbering counties. Moments shared in song forged common ground between performers and audiences of diverse backgrounds. At the same time, the lyrics and origins of folk music sometimes echoed tensions and differences within local communities.

Music came to the mountains from an array of sources: European ballads and local songwriters, slave plantations and fishing fleets, printed sheet music and oral transmission, phonograph records and minstrel shows. Music also left the Mountain State—as folks who moved elsewhere took their songs with them and as many old-time musicians passed on.

Though only a handful of tunes directly address industrialization, the underlying themes of many folksongs from this period help reveal the transformative impact of the timber boom on the identity and culture of the West Virginia highlands.

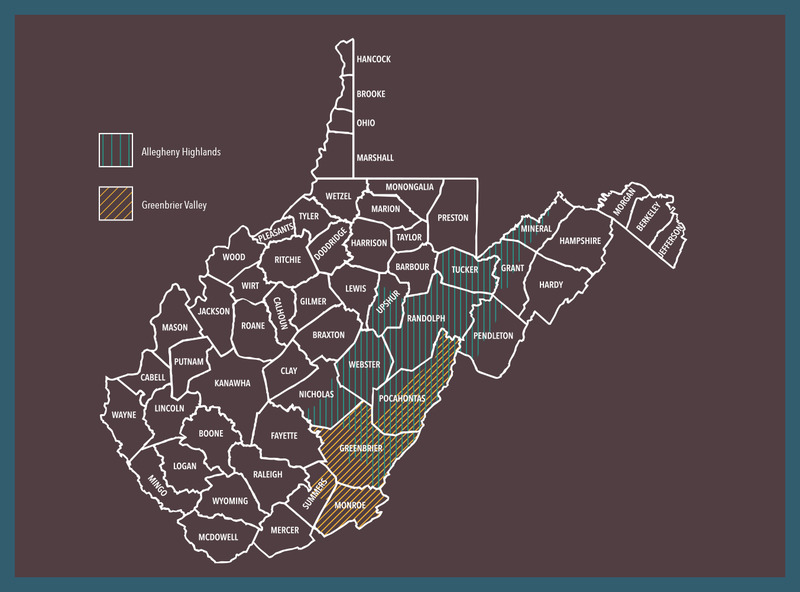

Two overlapping, regional designations play essential roles in this history of West Virginia’s timber industry.

Home to a magnificent variety of hardwoods and softwoods, the Allegheny Highlands include the highest peaks in the Allegheny Mountains. Today, much of this area is part of the Monongahela National Forest.

The counties of the Allegheny Highlands are fed by multiple river systems, one of which forms the Greenbrier River Valley. The river systems, and later railroads, connected the Greenbrier Valley with the Allegheny Highlands, forming a transportation and trade network that also linked the region to neighboring counties, such as Braxton and Clay.

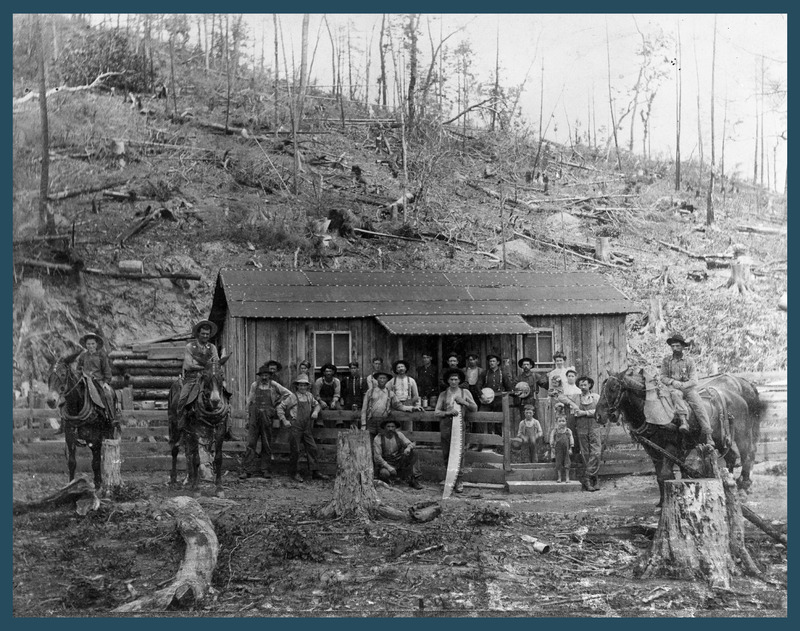

Notice the loggers holding banjos at this Pocahontas County logging camp. Fiddles and banjos were the most common instruments in traditional Appalachian music for many decades; guitar accompaniment did not become popular until the twentieth century.

“Folkloric documentation can serve as a mirror to show us the culture we have, but also what we've lost and gained along the way, for better or worse.”

Emily Hilliard, West Virginia State Folklorist

A native of Pocahontas County, W.E. “Tweard” Blackhurst was a high school teacher, conservationist, and author of popular novels about the timber industry, including Riders of the Flood and Sawdust in Your Eyes.

Like Blackhurst, Dr. Roy Clarkson was raised in Pocahontas County and experienced the impact of the timber boom firsthand. His love of the mountains led him to a career as a botanist, WVU professor, and writer of two well-known regional histories of the logging industry, Tumult on the Mountains and On Beyond Leatherbark.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, the practice of “song catching” took hold in Appalachia as music scholars sought to collect and preserve mountain music with Anglo-Saxon origins. This focus on English ballads skewed outside perceptions of Appalachia’s musical heritage by reinforcing stereotypes of the region as an isolated, all-white enclave.

By the 1920s, some scholars and folklorists—often born or living in Appalachia—began expanding the scope of music scholarship in the region beyond just Old World ballads. However, they continued to neglect certain types of songs—like banjo tunes, church hymns, and commercial hits—and largely ignored the music of black and immigrant communities.

During and after West Virginia’s timber boom, folklorists and scholars used recording devices and written transcriptions to collect songs throughout the state. Their individual biases and reasons for collecting all varied, but their collective work brought new insight into the meaning and makeup of West Virginia’s folksong traditions.

In addition to songs collected by these folklorists, this exhibit incorporates the music of several well-known Appalachian musicians, both living and deceased. Having learned partly or fully through oral transmission, their repertoires are broader than the transcriptions and recordings of the twentieth-century folklorists.

We will never know what rich musical heritage has been lost to the passage of time—but recent focus on the diversity of music-making in Appalachia invites opportunities to highlight previously unheard voices.

“They are called folk songs because they belong to the people and not any one individual.”

Patrick Gainer, folklorist | Folk Songs from the West Virginia Hills

Though often viewed by the popular press as backward and isolated, historians have consistently shown that Appalachia was connected to the broader national economy and culture. Often following the lead of middle-class reformers, many residents came to believe that both education and industrial development were essential to the advancement of the region. As part of their pursuit of education, some rural communities offered subscription singing schools where adults and children could learn to sing using a form of written music called “shape notes.” Families paid a subscription fee to compensate a traveling music teacher for group lessons that ran about two weeks.

“When we have the opportunity to engage with the voices from the past, our understanding of history is significantly improved.”

Travis Stimeling, musicologist | The Country Music Reader

"In West Virginia, music has a long history, but little is reflected in written records from the nineteenth century or earlier...Oral accounts of older generations remain the richest sources for interpreting the winding path that musical traditions have traveled in the region up to the present time."

Erynn Marshall, fiddler and scholar | Music in the Air Somewhere: The Shifting Borders of West Virginia's Fiddle and Song Traditions