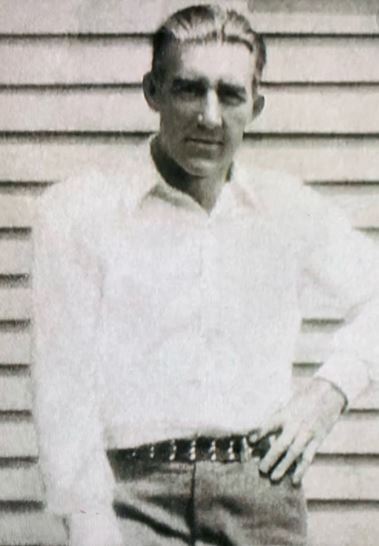

Dick Justice

The music of Dick Justice is known to us because in Chicago on 20 and 21 May 1929 he recorded eight songs for Brunswick Records. Of these six were released: Old Black Dog, Little Lulie, Brown Skin Blues, Cocaine, Henry Lee, and One Cold December Day. With Kanawha County fiddler Reese Jarvis he recorded four more on 20 May and these were issued under the name Jarvis Justice: Guian Valley Waltz, Poor Girl’s Waltz, Poca River Blues, and Muskrat Rag, all mainly instrumental dance tunes with some vocal interjections. In later interviews, Jarvis said that the two of them had never played together before arriving at the Brunswick studio. But in any case they seem to have gotten into a groove together as they played those four tunes in Chicago.

The innovatotive music Dick Justice made brought together several different influences: ancient Scottish ballads handed down through his family for generations as unaccompanied songs, blues guitar techniques and blues and pre-blues music learned from and with the Black musician Bayless Rose with whom he often played, from records made by other 1920s blues musicians, and mountain banjo songs.He is known to have played at dances and other events with Logan County musicians Frank Hutchison, banjo player Aunt Jenny Wilson, the Williamson Brothers Curry, fiddlers Pete Hill and Sherman Lawson, among others.

Mr. Justice’s place in the pantheon of American vernacular music was doubly ensured when Harry Smith selected his Henry Lee as the first track in his 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music , a six-LP compilation of 1920s and early 1930s recordings that jump-started the folk revival.Frank Hutchison’s Stackalee and the Williamson Brothers Curry Gonna Die With My Hammer In My Hand were also included in the Anthology. Thus three of the eighty-four tracks on this influential compilation came from Logan County.

Henry Franklin “Dick” Justice was born 2 April 1903 at East Lynn in the Stonewall district of Wayne County. In 1900 his father Frank Justice was described in the census as a day laborer on his grandfather’s farm there but by 1910 he was a coal miner in that district. By 1915 Dick’s family had moved to Lorado on Buffalo Creek in Logan County so apparently like many mining families there was a movement from place to place as men searched for better working conditions and wages. In 1917, his father was working for the Guyandotte Coal Company at Kitchen in Logan County. And in 1920, Dick was back with his parents in the Stonewall district and both he and his father were miners there once again but in 1921 they were in Stone Branch, Logan County, a mile and a half north of Kitchen along the Guyandotte River.In 1930, the year after his music was recorded in Chicago, Dick was a coal loader in Henlawson, Logan County.In 1940 he was a motorman in a mine at Cora, Logan County, and had two children, a son and a daughter.On his WW II draft registration card he indicated that he was living in Mount Gay, Logan County, and working for the Eagle Mines.

Mr. Justice died on 12 September 1962 and at that time he had been living at Yolyn on Rum Creek in Logan County, working as a miner at least from 1957, and he had been on Rum Creek since at least 1947.He was buried at the Yolyn Cemetery, alongside his son Dallas who had died in 1955 at the age of ten, having been injured at a fire in Slagle, also on Rum Creek, where Dick had worked for a time for the Amherst Coal Company.

I was able to visit the grave of Dick Justice in 2019, in the company of Chris Haddox and Brandon Kirk. Chris recently wrote this about how he located the grave:

"By 2000, the location of Dick's grave site had long been forgotten by his son and daughters. It had been years since they had visited the grave, and they had wondered if coal mining activity had destroyed the small mountainside cemetery."

In 2018, Chris Haddox sought to locate the grave to pay his respects to his fellow Logan County musician. After serval hours of poring over maps, driving up and down Rum Creek, and stopping to talk with a few long-time residents of the Yolyn area, Haddox finally found the cemetery. The pathway leading to the cemetery was anything but obvious, and the cemetery itself was so overgrown that the only clue he had that he was anywhere near a cemetery was the spotting of several old and decaying American flags scattered about from long past Memorial Days. Many of the stones in the cemetery had fallen and those that were still standing were so worn that it was difficult to read the inscriptions. There was no visible path leading to the little fenced in area where Haddox eventually found the headstone of Dick and his 10 year old son, Dallas.

—Gloria Goodwin Raheja, February 2021.

Sources: Gloria Goodwin Raheja’s research for her forthcoming book Logan County Blues: Frank Hutchison in the Sonic Landscape of the Appalachian Coalfields.

Watch

Go with Chris on his Dick Justice Grave Visit in 2018

Listen

Listen to Dick sing Henry Lee on Youtube

Listen to Dick and fiddler Reese Jarvis play Poca River Blues from Dick Justice

The Hunt for Dick Justice's Grave

For me, the hunt for Dick Justice's grave began with the hunt for Dick Justice, the living man. I had been searching for information on him since I first picked up a CD at Backstreet Records in Morgantown, WV in 1998.The CD was titled, 'Old Time Music from West Virginia' and the owner of the store, knowing my musical interests, suggested it to me. In addition to the cuts by Dick Justice, the CD included cuts from Logan, WV musicians Frank Hutchison, with whom I was familiar, and The Williamson Brothers and Curry. I was blown away by all of the music, but the playing and singing of Dick Justice just put me over the edge. How could I, a Logan, WV born and raised guitar player and singer, have never heard of Dick Justice? As I was not getting back to Logan very often at that time, I found it difficult to connect with anyone who might have known about Dick Justice.

The liner notes on the CD I bought mentioned an African-American fiddler named Pete Hill who played with Justice. As the liner notes mentioned that Dick had lived in Henlawson, a small coal camp less than a quarter of a mile from where I grew up in Mitchell Heights, I started my search for Dick by brow beating several folks I knew in Henlawson for information on either Dick or Pete. I called musician friends, I called friends with the Justice surname, and I called several local historians, but kept coming up dry. Sadly, I was completely unaware of Harry Smith’s 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music that kicked off with Dick Justice singing Henry Lee, and included Hutchison and the Williams Brothers and Curry. I later learned that Pete had no connection to Henlawson, but rather he was from down on Sawmill--another part of Logan County. I’ll write up more on my hunt for Pete in another story.

As the years passed the idea of learning more about Dick was always in the back of my mind. As I became more aware of online resources I would occasionally do searches to see if I could turn up anything on him, but I was not very thorough in my approach, nor was I aware of the range of resources that were available. Once while teaching a guitar workshop at the Augusta Heritage Festival in Elkins, WV, I performed Dick’s Old Black Dog—a song he apparently learned from Bayless Rose, a black bluesman from Kentucky whose railroading job regularly brought him through Logan.

In 2013 I stumbled upon some resource that I now cannot recall--most likely his death certificate--indicating that he was buried in the Yolyn Cemetery. Yolyn was one coal camp in a string of others on Rum Creek in Logan County. While I knew where Yolyn was, I was more aware of its proximity to Dehue. Dehue, as did so many other small communities when I was growing up, had a grade school and we used to roam around to these little schools to play basketball in the gyms in the evenings. Additionally, Rum Creek led up to Kelly Mountain (perhaps more accurately names Lowe's Mountain)--a prime berry picking spot. One had to pass through Yolyn on the way to Kelly Mountain. The location of the Yolyn Cemetery, however, was not immediately known to me, so I brought up that great tool, Google Maps, and was able to ascertain a general location of the cemetery.

Anyone who has used Google Maps images, or any aerial photography in general, knows that things on the ground can look very different than they do from above. I found a spot that I believed to be the Yolyn Cemetery, but it was just a spot on a wooded hillside--there was nothing in the images that confirmed a cemetery at that location. So, I also took stock of other nearby landmarks, one of them the Chambers Cemetery as it was very visible and lay downstream of Yolyn where Mudlick Branch joins Rum Creek. For all I knew, the Chambers Cemetery could have been known locally as the Yolyn Cemetery. I made a mental note of the landscape and then got sidetracked by other things such as family and work!

In 2018 I was teaching a place-based songwriting class for 4-H campers in Wyoming County, WV. Wyoming County and Logan County share a border, and the camp itself, The Roscoe Plumley Wyoming County Youth Camp, sits only fifteen air miles (40 driving miles) from Yolyn. As my class was in the morning, I was able to use my free afternoons revisiting and re-familiarizing myself with my old stomping grounds.

Heading over to Logan to visit my sister, I saw the turn for Rum Creek and the hunt for Dick Justice’s grave was again front and center in my mind. It had not even occurred to me to look for it on this trip, but I suppose Dick had other plans and in an instant I was making the turn. This was my first trip on the “new” four lane road that connected the towns of Logan and Man, giving travelers a quicker and less adventurous route to travel as compared to the old state Rt. 10. From upon on the new road, the cut through the mountain into Rum Creek looked like an ancient gate guarding the entrance to some long-forgotten world.

Armed with little more than old memories of driving up and down Rum Creek as a teen, and a more recent, but nearly five-year old image of an aerial view of the road up to Kelly Mountain, I crossed through the gate and began what would be a several hour exploration that brought me into contact with two living humans and three cemeteries.

Upon passing through the rock cut gate an onto Rum Creek itself, the first thing I noticed was how different it looked as compared to how it did in my memories. I understood the changes in the coal economy and didn’t expect to see the exact scenes in my mind, yet I was somehow still surprised. Gone were the strings of homes, the mom and pop stores, the people out and about. What remained were a few clusters of homes here and there, a few old buildings, a large coal prep plant, and a creek choked with Japanese Knotweed.

As I headed up the creek I passed by Dehue-Chambers grade school. A short distance later, I was passing through and under the Bandmill coal complex. Before long, I noticed a big cemetery on the hillside to my left—the Chambers Cemetery. My mind checked a box that I was now in the general vicinity of where I thought Dick might be buried. I decided to drive on up the creek to see if I might locate other cemeteries. The next cemetery I encountered was all the way up the mountain—the picturesque Lowe family cemetery. In my mind now, Dick was either in the Chambers Cemetery, or he was in some forgotten and grown over plot between the Chambers and Lowe locations. As I slowly drove back down the holler toward the Chambers Cemetery, I scanned each steep hillside looking for anything that might suggest another cemetery…an opening in the trees, an old road entrance, a pull-off spot…anything. I did turn into one small pullout, parked, and walked about for a bit, but saw nothing that encouraged me.

I passed the Chambers Cemetery again, then turned around and drove back up to where I could pull off the road. Checking for dogs—I always check for dogs—I made my way up to the cemetery and methodically went through the stones row by row looking for Dick. Though the cemetery was well-maintained, I did notice some stones around the upper edge in the woods, but none of those marked Dick’s grave.

As I walked around I noticed that I was being watched by a few men from the house down on the creek near where I had parked. I waved at them, they waved back, and I once again went round the cemetery. While Dick was not to be found here, I did take some pictures of a wonderfully large Tulip Poplar tree in the center of the cemetery, as well as a picture an interesting homemade stone of marbles set into concrete and marking the grave of a person named Lucille Ball.

Convinced that Dick was not in this cemetery, I returned to my car and again drove slowly up the creek looking for another likely spot. Just before the spot I had pulled into on my trip down from the Lowe Cemetery, I noticed the smallest of breaks in the vegetation. I looked at it from the road for a few minutes, then went up to the first spot I had explored, turned around and made my way back down the house where the men had been watching me.

I pulled onto the little road that led up beside the house and parked my car. No one was outside, so I made a few “anybody home” calls out loud and heard a voice from behind the house respond. I rounded the house to find fellow sitting on his covered back patio shooting things in the yard with a pellet gun. We said our hellos and he, Mr. Sargent, asked me if I found the grave I was looking for up on the hillside. As I related the story of my search, he told me that he did not recognize the Dick Justice name, and suggested that I go a few houses down the creek, pointing out a red roofed house a few hundred yards away, and talk with his grandad—the caretaker of the Chambers Cemetery and a general historian of the burials around here.

We chatted awhile about this and that, then I asked him if there was a Yolyn Cemetery, or if the Chambers Cemetery was also known as the Yolyn Cemetery. “Oh, man, he said, I’ve not thought of the Yolyn Cemetery for a long time. There’s not been a burial up there since I was a kid, and I’m nearly 60 now.” With that my pulse quickened. I suggested that I must have passed it on my way up to the Lowe Cemetery, and he confirmed that notion, telling me to “go back up the creek until I crossed it a fifth time from his house. Right after that fifth crossing there’d be a small spot to pull into—where an old road came down from the mountain. The cemetery would be “up in there somewhere.”

I mentioned that I had seen the spot I thought he was talking about, then told him about the other spot I had poked around some. He said, “yep, that other spot you went to is on past where I’m talking about…just come back this way a bit, but don’t cross the creek—it will be on your right as you are coming back down.”

He again suggested that I talk with his grandad, something I said that I’d do if this new lead didn’t turn up anything. We said our goodbyes and he offered up these words in closing, “watch for snakes up there, buddy, it is thick with copperheads and rattlers.” I was really more cautious about ticks, but I heard him loud and clear, and wondered to myself why this added to the adventure.

I drove back up the creek, counting the crossings, until I came to the fifth, and there on the left was the potential opening. As I had yet to even see another vehicle pass in the hour or so I had been going up and down the creek, I stepped out of the car to determine the feasibility of pulling my small rental SUV into this place without dropping into some roadside ditch from which I’d not be able to get out. Having determined it was safe, I pulled into the space…barely able to get the car completely off the road.

After busting through the brush a bit, I could tell that I was on what looked to be an old washed out timber or gas well road. Before too long I spotted a little gas well shack in the distance, so I hiked up to it and had a look around. The road up which I came had not seen a vehicle for a long time, being now more of a wash than a road. I could not see anything that looked like a cemetery, but reasoned that if any bodies were buried up this way, they would have been carried up by pallbearers, and what a steep carry it would have been.

Convinced I was in the place he told me to look, but not convinced there was a cemetery anywhere near, I went back to his house. We chatted some more and he confirmed I was in the right place. I mentioned the gas well shack, and he wasn’t sure about that. I said how the road went straight up a small drainage and he couldn’t recall just how far up into the woods the cemetery lay. It was up there, though, he assured me.

Back up to the fifth crossing and to the little opening that was now a tad more open from my earlier entry. Back up to the gas well shack. Back to the same “this does not look good” thoughts in my head. The vegetation was thick and I was asking Dick out loud to give me some clue as to whether or not he was somewhere near. I turned and slowly walked back down to my car, thinking I’d better go talk with the man’s grandad.

I parked my car in what appeared to be a shared driveway for the red-roofed house and that of a neighbor. A man cutting his grass, a Mr. Lowe, could tell I was looking for something and came over to my car. I explained who I was seeking and Mr. Lowe told that he was in town for the afternoon.

Mr. Lowe commented that he had seen me drive by earlier and I related the reason. I asked him about the Yolyn Cemetery, and he had almost the identical response as Mr. Sargent, “there’s not been a burial up there since I was a kid,” I kid you not! I told him I’d already poked around a bit, but wanted to make absolutely sure I was in the right spot, which he confirmed that I was. I told him I was going to go back up, but needed to find a good stick before I got too deep in the thickest of the growth. With that he went to his garage, returned with a stout stick, and said, “watch for copperheads.”

The humidity was very high, and the temps pretty warm, prompting him to ask me if I wanted some water to take with me. He returned with two bottles of water, some peanut butter crackers, and well-wishes for my hunt. I asked if he’d do me one more favor. “As you and Mr. Sargent are the only two people who know exactly where I am at the moment, if you don’t see me head back down the creek sometime this afternoon, would you come look for me to make sure I’m not laying up there swollen up from some snake bite?” He chuckled a bit and said he had a few more hours of grass cutting and if I was not out by then, he’d come looking.

Back up to the fifth crossing and into the woods. Back up to the gas well shack. Back to asking Dick Justice to give me a sign. Looking back down toward my car, I scanned left and right—something telling me that I needed to be looking side to side, rather than farther up the washed out road. I walked about halfway back down to my car and noticed some disturbed ground to my right, nothing more than a little deer path going up the side of the drainage. I followed it with my eyes, then with my feet.

It was a scramble up the bank, but after 30 feet or so I reached a little plateau that had gone unnoticed earlier. My eyes were drawn to a beautiful big Beech tree to my left, then a bit to my right and slightly above my head, I spied a small, dirty, ragged American flag—a reminder of a Memorial Day gesture from long ago.

I stood in silence for a bit, allowing the scene to slowly reveal itself. The faded red, white, and blue of another flag appeared in the greenery. More flags appeared, then a stone. Other stones appeared where none were before—some with inscriptions, some leaning heavily, some fallen over, some just field stones. The long straight edge of a low concrete wall suddenly looked out of place among the vegetation, appearing to be the berm of a family plot. More flags. The rusted remains of a metal sign. All of these things that just moments earlier were thirty feet away and invisible were now impossible to overlook.

I believed Mr. Sargent and Mr. Lowe’s assertions that this place had not seen a burial since they were kids. There was no order to things, no clear arrangement of rows, the concrete plot seemed the anchor of the cemetery, with all other markers just scattered wherever there was enough room to bury someone.

There were maybe eight to ten stones in the first little area I perused, but none were marking Dick’s grave. I noticed some snapped twigs on a spicebush, and walked up in that direction. After busting through some more growth, I was surprised to find a grave that appeared to have been recently cleaned up. The stone was in good shape, and the date of death was marked as 1942 (perhaps it was a new stone for a previously unmarked, or poorly marked grave). There were three crosses in the dirt near the grave, and the grave itself sat in its own little patch of vegetation, somewhat isolated from any others. Still, if the stone were newer, there was no clear evidence of how the family would have brought the stone to this spot, I it was hard to imagine it being carried up the way I came.

A few more stones, some unmarked graves, but no Dick Justice.

That Beech tree was quite nice, so I walked back down to it, looking for any missed stones along the way. There I stood beneath that tree and I said quite loudly, “OK, Dick Justice, if you are in here, reveal yourself.” There was no visible reason to start walking in the direction I did—toward the hillside—but something said to just start fanning out. With one eye on the ground looking for snakes, and the other looking ahead for a hidden stone, I moved beyond the aforementioned low concrete wall toward the mountain and into the thickest growth I had yet encountered.

Reaching out to move a branch I noticed something that was both darker and straighter than the surrounding vegetation. A few more steps and I was able to identify it as the top of a very rusted wire fence. As I got closer, I could make out the entirety of a fenced-in enclosure, and there in the back right corner sat the stone marking the grave for Dick. To his right sat a smaller stone adorned with a carving of a lamb. This stone, I later learned from one of Dick’s nephews, marked the grave of Dick’s infant son, Dallas. Dallas died at the age of ten as the result of a horrible accident in Dehue. The nephew indicated to me that this incident devastated Dick and resulted in his becoming a man of the Lord.

To my right I noticed the gate to the enclosure and I stepped inside, both excited and a little sad that the hunt was over, and half expecting to hear a distant refrain of Henry Lee or Old Black Dog wafting up from the grave.

I've since returned to the gravesite a few times and things are noticeably different--a powerline right of way on the uphill edge of the cemetery that I could not even see on the first visit has been cleared, exposing even more graves. Someone has straightened up the overturned stones, and there are new flowers on many of the graves. Following my initial visit, I heard from a young man from down in Kentucky. He had seen my video post of the gravesite visit and was excited to know where the cemetery was as he and his dad liked to travel around to these spots and clean things up. For whatever reasons, it seems that Dick Justice, and the others who rest on that hillside, are back into current memory.

-- Written by Chris Haddox, May 2021